The use of colour in film remains one of the longest and richest currents in the history of motion pictures. From tinting to toning, filmmakers have tried several incredible techniques to introduce colour into moving images almost since the medium’s beginnings. One special process that developed after a few decades was Kodak Kodacolor, which utilized lenticular technology to create a three-tone colour representation. Only produced for four years from 1928-1932[1], the Archives is lucky to house some of these rare and special films.

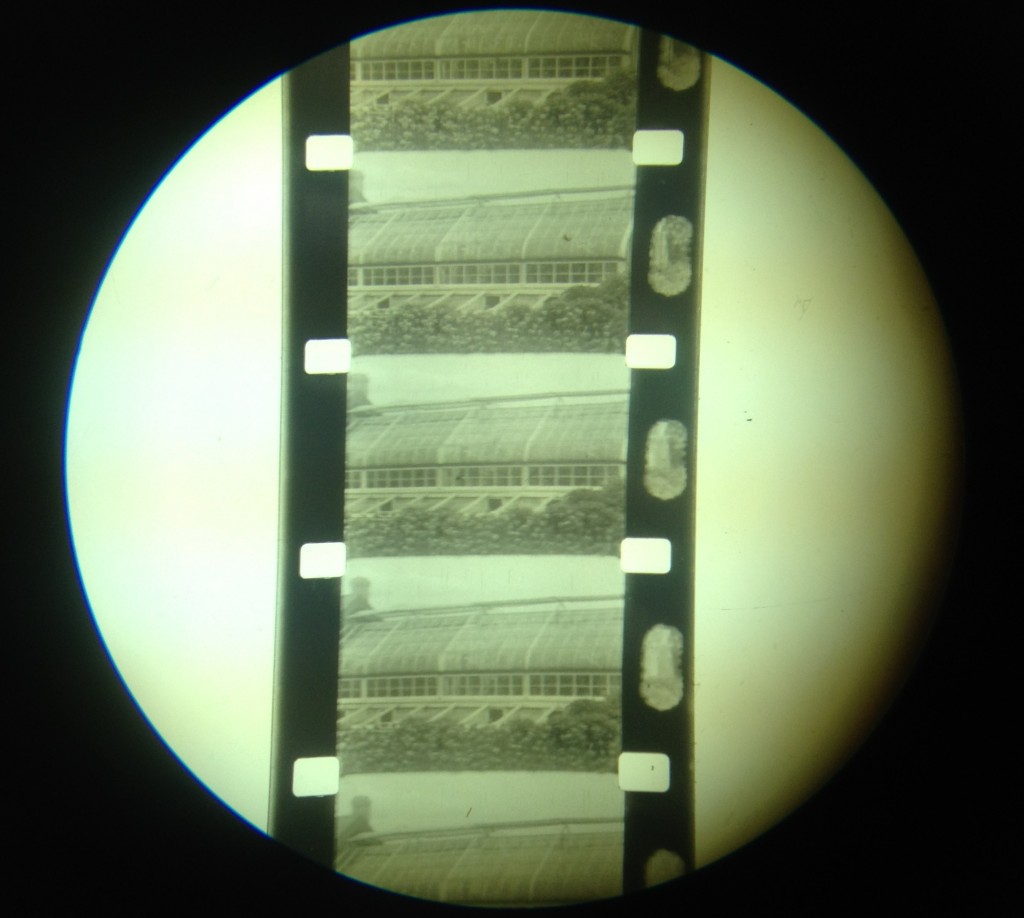

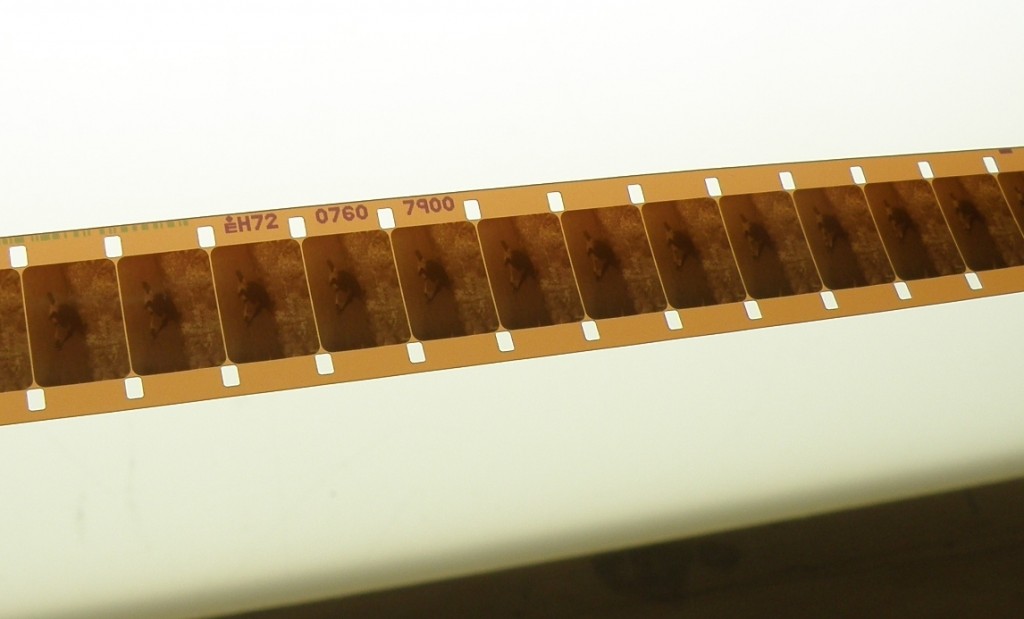

Looking directly at the film with a naked eye, it appears no different than regular black and white 16mm film. This is because the colour information is encoded into a black and white film: no coloured dyes are used.

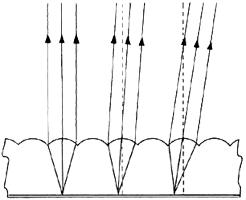

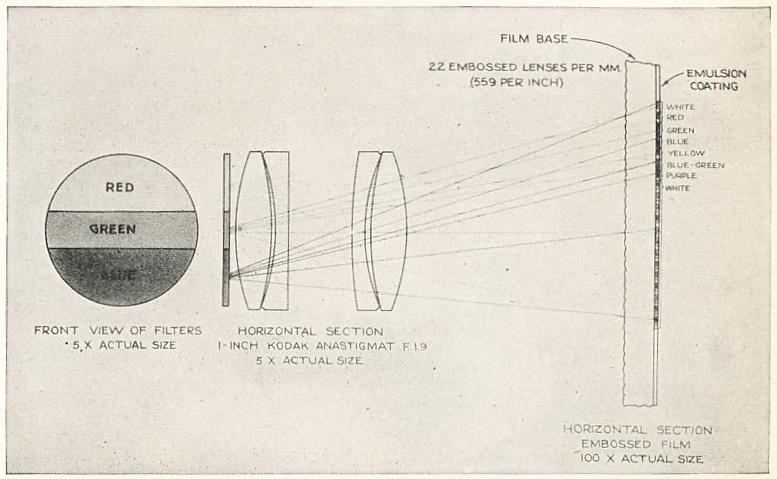

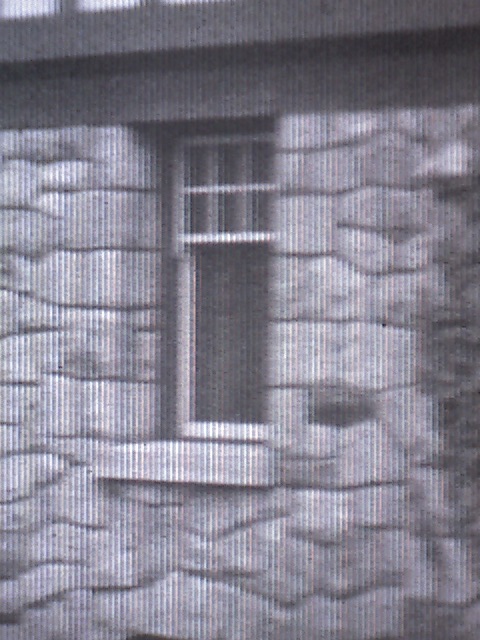

The plastic base of the film, as opposed to typical acetate film stock of the period, was created with tiny lenses (called lenticules) embossed into it. When shooting, the film passes by the camera lens with the base (lenticules) facing toward the subject, and the emulsion (where the image is captured) facing away. This way, the light passes through the film’s lenticules before creating the image on the emulsion. The camera requires a special lens which splits the light into three separate bands of red, green, and blue, which are then captured in the lenticules.

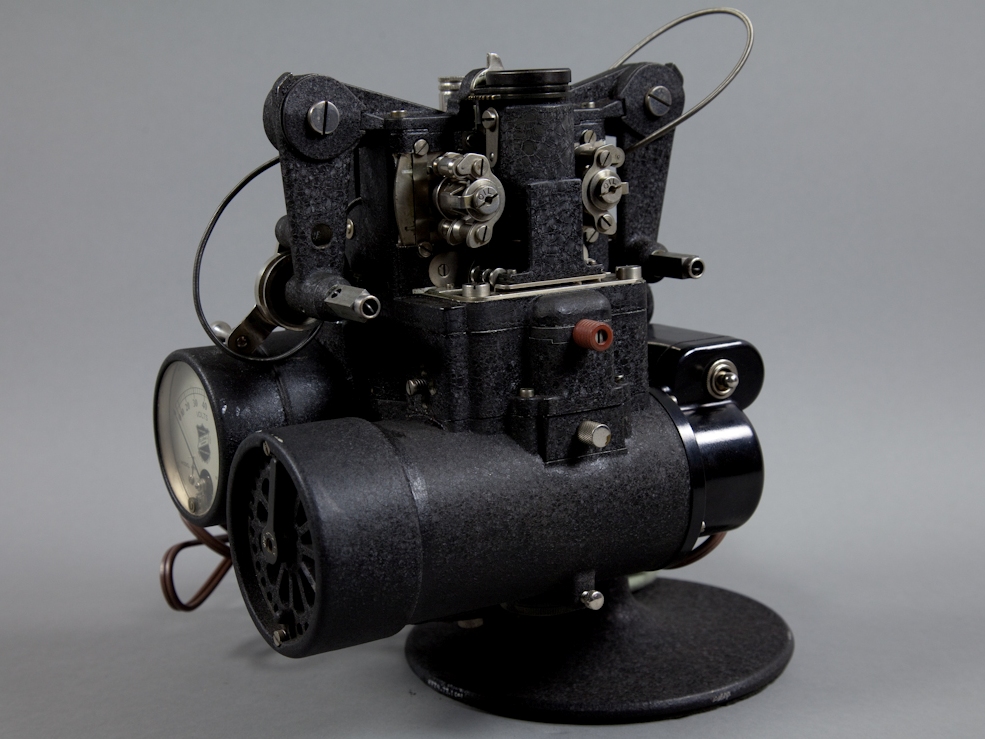

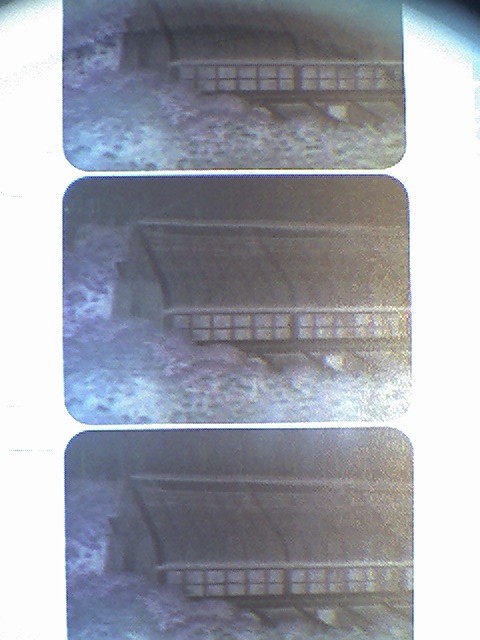

Each frame of film contains many patches of information which each contain the red, green or blue part of the image for that area of the frame. This film requires a similar lens to add the red, green or blue patches back together (known as additive colour) and produce a colour image. Without this special lens the films can still be projected, though they will appear simply as a black and white film. The Museum of Vancouver has such a projector in their collection, seen above.

Our lenticular films, entitled Gardens at Aberthau (Reference code AM1470-: MI-58) and Children and animals at Aberthau in garden (Reference code AM1470-: MI-43) are part of the Colonel Victor Spencer family fonds. The Spencer family owned a home at 1750 Trimble Street in Vancouver, known as Aberthau. We have 69 amateur films shot by various members of the Spencer Family from the 1920s to the 1960s.

When it came time to digitize the films, we had the work done by Film Technology Company in Los Angeles, the only lab in North America still able to transfer lenticular film. In addition to the digitized copy, we also created a polyester colour negative as a preservation copy.

Photo by Jesse Cumming.

Photo by Jesse Cumming.

We’re always interested in acquiring more film documenting Vancouver’s past, even on complicated and rare formats such as lenticular Kodacolor. If you know of any film you think we might be interested in acquiring please do not hesitate to contact us.

[1] In 1942 Kodak began producing a still colour negative film also called Kodacolor, though it is unrelated to the earlier lenticular moving image film stock.

Back to article

Hello!

I work at Cineteca Nacional in Mexico City a FIAF Member, and this article is amazing!!

I have a question: in this case, for the lenticular kodacolor. The only way to find out that a black and white film maybe a lenticular kodacolor is by taking a picture under a magnification?

Does the film material have some other kodak marks or labels visible?

If it’s a black and white reversal film with “Kodacolor” edge printed, then it’s probably lenticular. Viewing it under sufficient magnification should confirm this, or identify it if the edge marking is not present.