Recent processing work focusing on our architectural records holdings have revealed the variety of fascinating perspective renderings we have in our various fonds and City records series.

One of the more spectacular examples is the Francis Maw rendering of the design for the expanded Hudson’s Bay Company store at Granville and West Georgia streets, in the heart of downtown.

It was created for the architects, Horwood and White, most likely from the design drawings rather than the building itself. It was retained by the architects until its donation to the Archives.

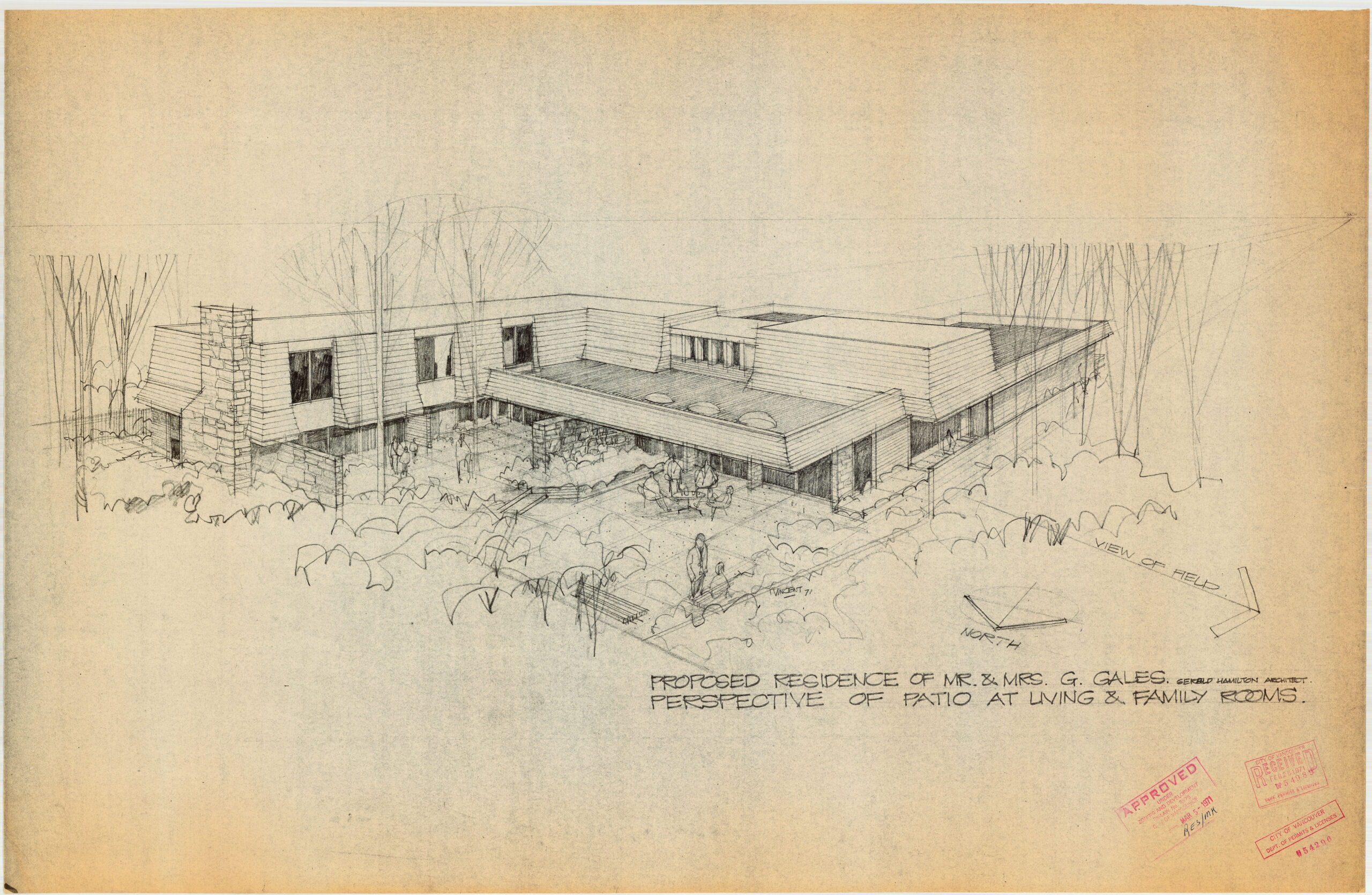

Perspective renderings are architectural drawings, often made by specialist architectural artists, to show the design of a building exterior or interior, garden or other structure, in a naturalistic setting. Functionally, renderings site the designed structure in its immediate environs and usually show it in use, rather than as the decontextualized, empty spaces depicted in floor plans and elevations. The following drawing, while created to show Gerald Hamilton’s design of the Gales residence, also features the extensive gardens being used by figures representing the clients.

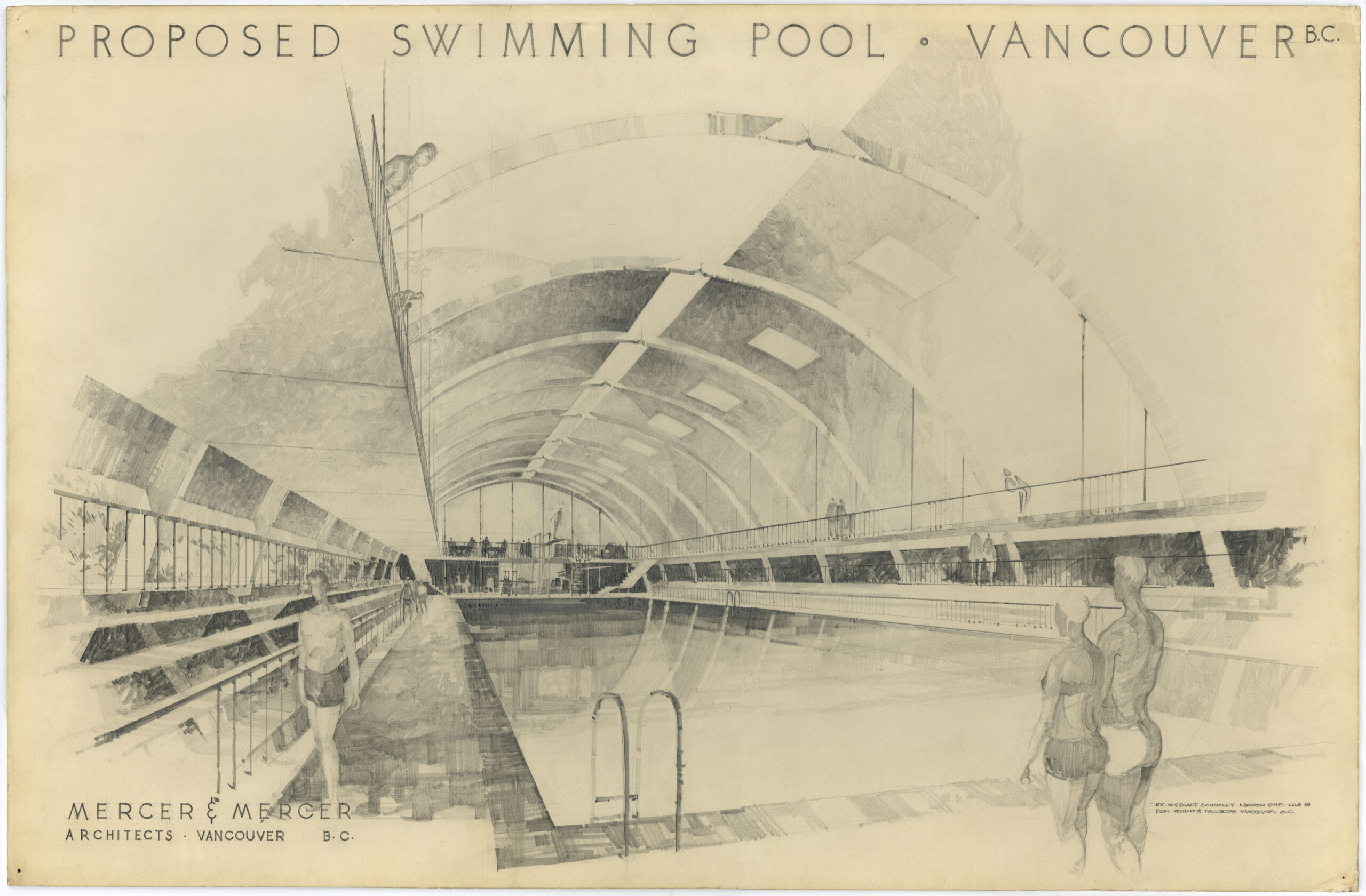

Interior perspective renderings will show an entire room or public space with the designed elements—walls, ceiling, floors, windows and finishes—working together, as opposed to contract or construction drawings, which show these elements separately. A good example is the following drawing of Mercer and Mercer’s design for a public swimming pool building, likely for a community centre.

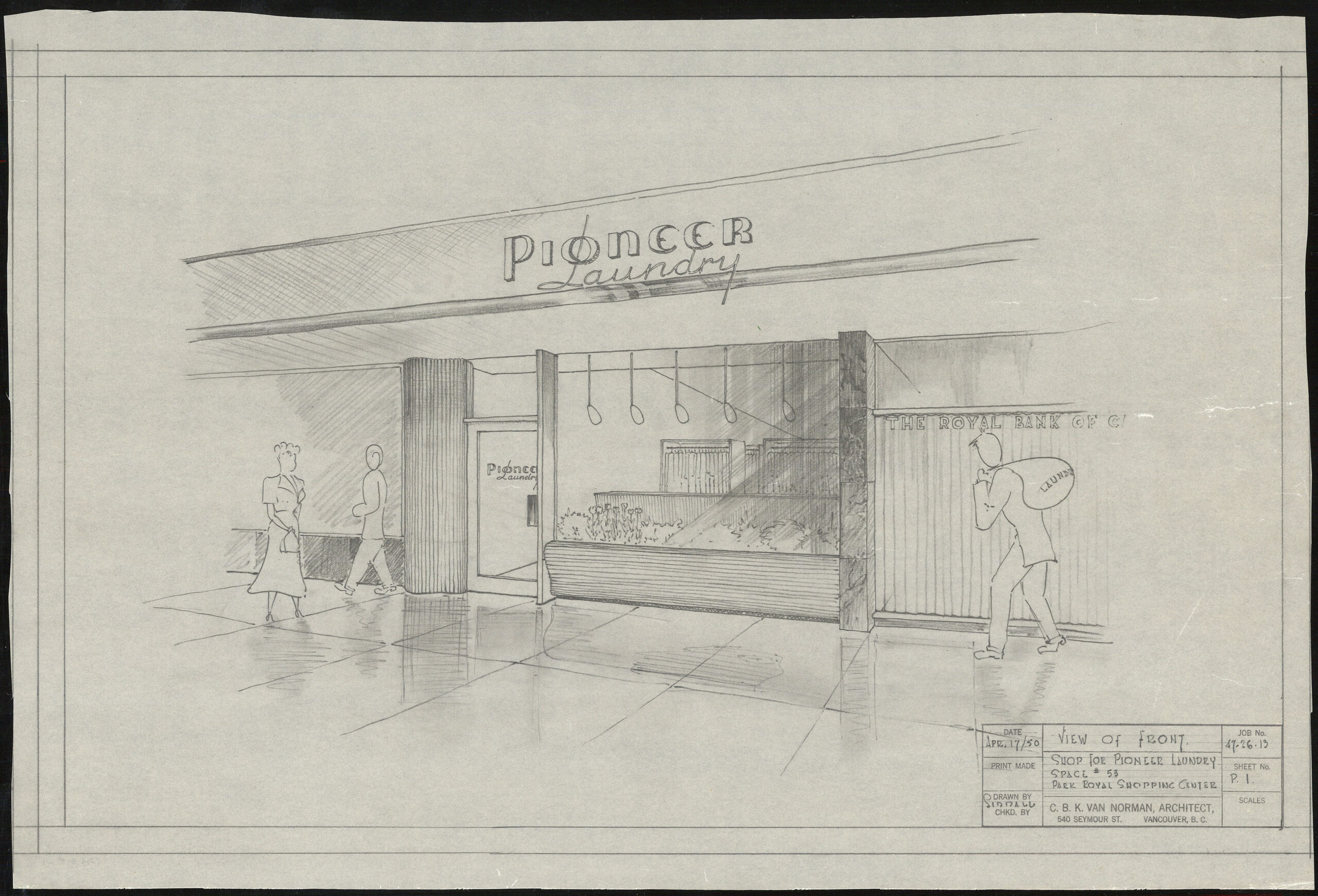

While most renderings are overtly perspective drawings, some are more akin to elevation drawings. The following rendering, from the C.B.K van Norman fonds, depicts the design of store frontages for the construction of Park Royal Mall.

Exterior renderings often include people, surrounding buildings, and the overall environment that the design will or does live within. These drawings depicts articulations of the architect’s creative imagination made accessible to viewers less fluent in the technical language of architecture. Their function is akin to a photograph, but of (usually) not yet built structures.

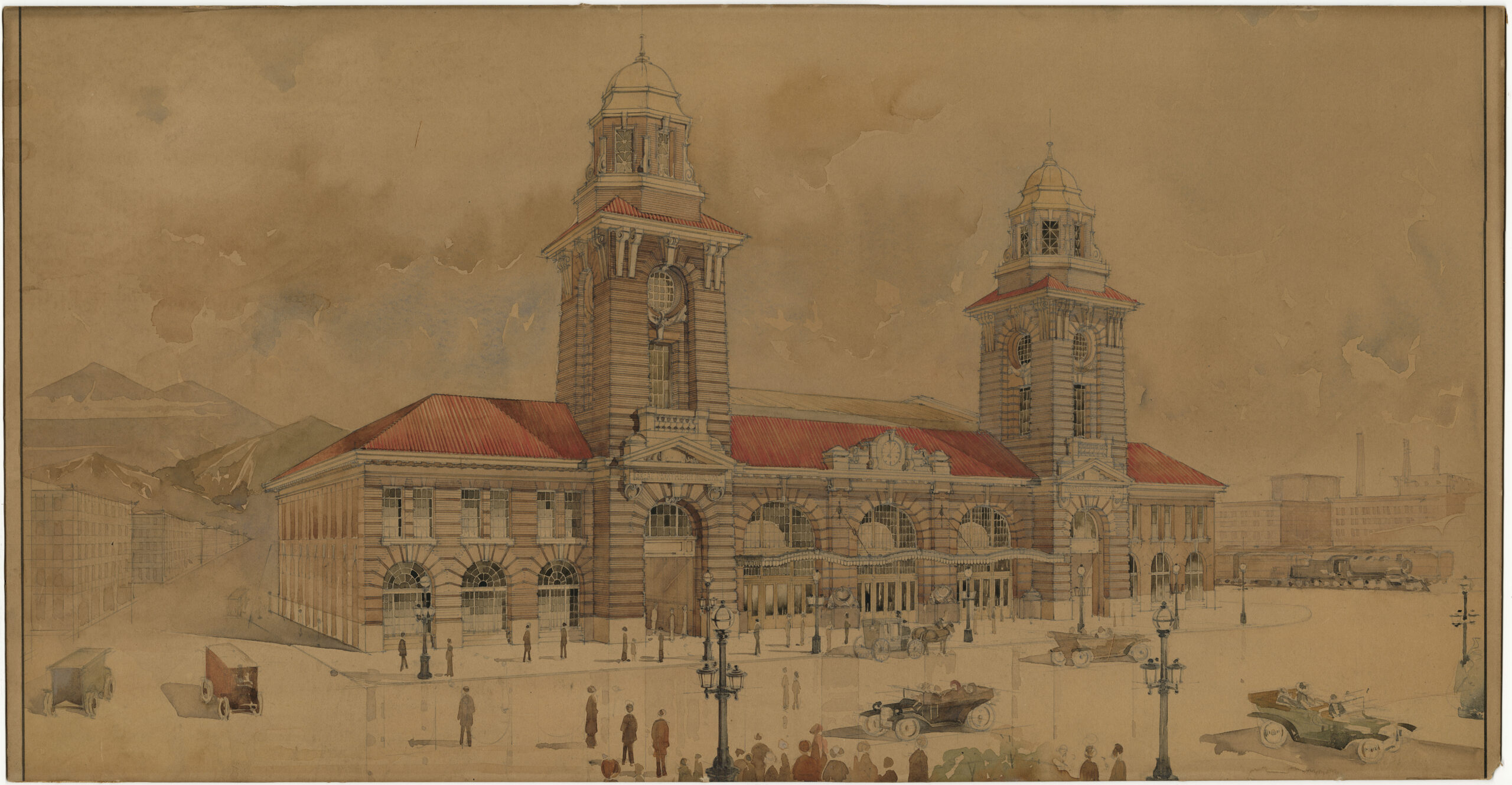

One of the earliest renderings in our holdings is the drawing of Fred Townley’s design for the Great Northern Railway terminal. The extensive details of not just the building but of the travellers and other members of the crowd in front of the station makes this rendering a standout among those in our holdings.

Renderings are created for a number of reasons; most commonly, they depict a design as part of a competition package to win a commission, to promote a design to a client, or as a show piece to promote the work of the architect (like the Hudson’s Bay Store rendering above).

In the case of the Townley drawing of the Great Northern station, we cannot know who executed it, or whether it was submitted as part of the competition package which won Townley the commission. The top and bottom of the drawing were trimmed off before we received it. The considerable care and detail shown indicates it may well have been a competition drawing, created by a specialist renderer.

One rendering which we know was created for a competition is the drawing of R.P.S. Twizzell’s design for the Canadian Memorial Chapel.

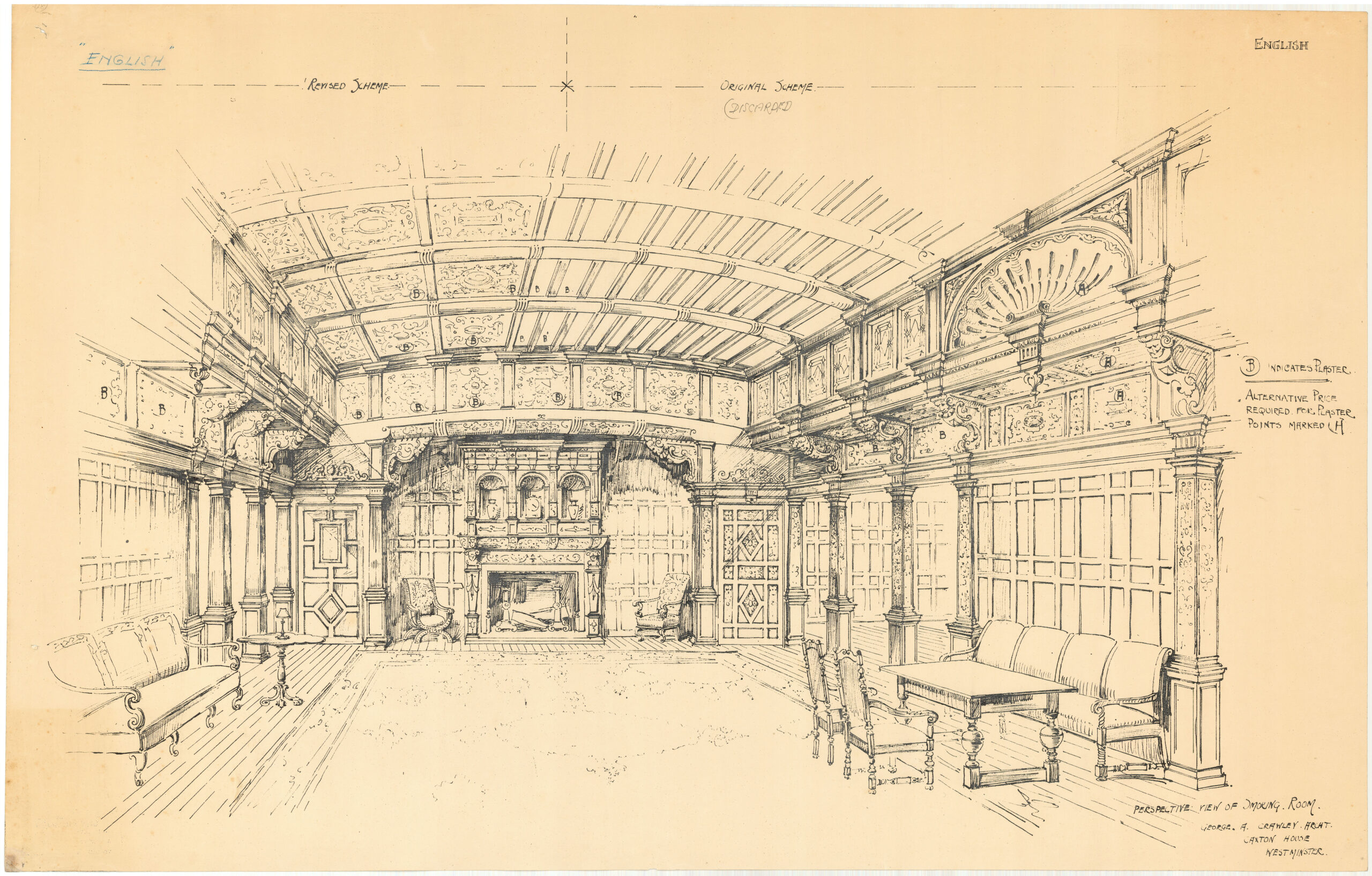

Perspective renderings are made for all kinds of designed spaces: buildings, landscapes, the interior fit-out of ships, large non-building structures such as bridges, or streetscapes. George Crawley’s designs for the first-class passenger facilities in two ocean liners for Canadian Pacific Steamships (most likely the Empress of Asia and Empress of Russia) are rare surviving examples of architectural design applied to the interiors of ships.

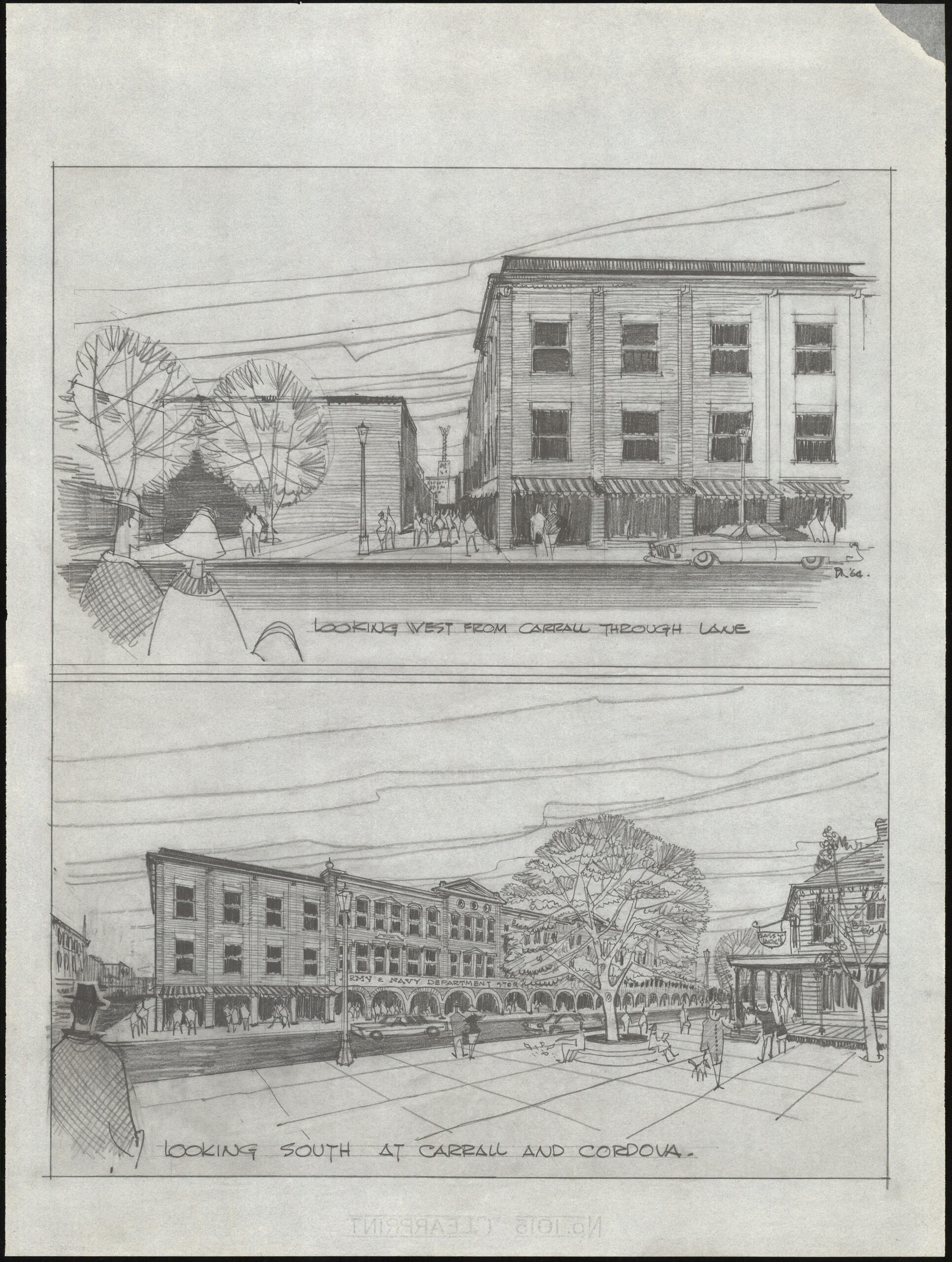

Perspective renderings have also been made for streetscapes, depicting a series of existing structures. The following example is one of Gastown, made by Vancouver Planning Department staff, likely in relation to the proposed heritage conservation of Maple Tree Square.

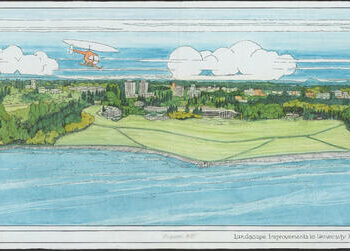

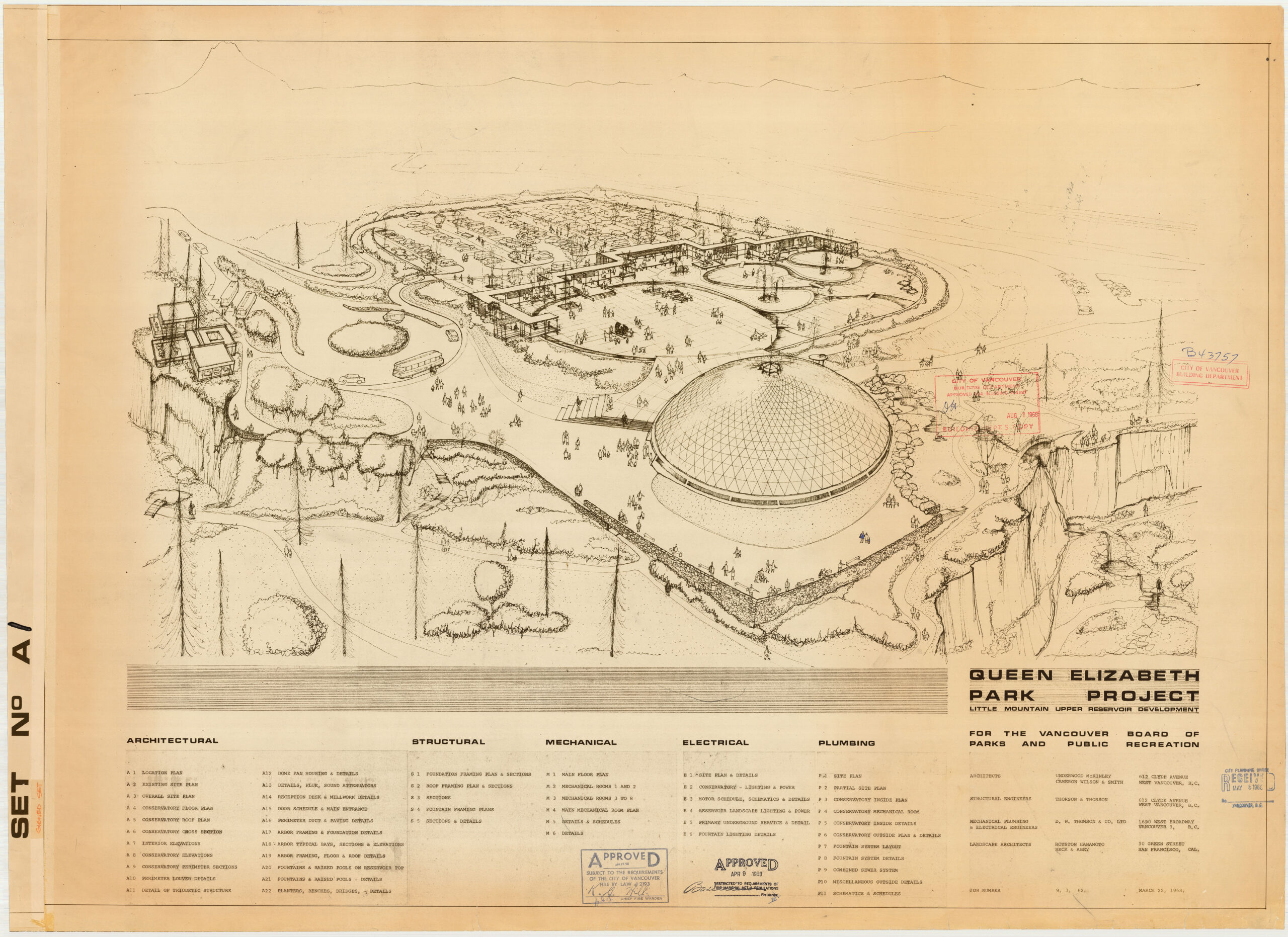

Over the course of the 20th century, it became more common for renderings to be created as part of architectural drawing sets, rather than as stand-alone drawings. These renderings were often incorporated into the first page of the set, with the site plan or the drawing index. The following aerial view of the Bloedel Conservatory in Queen Elizabeth Park is incorporated on the first sheet—the drawings index—of a set of architectural drawings submitted to the City in support of the building permit application.

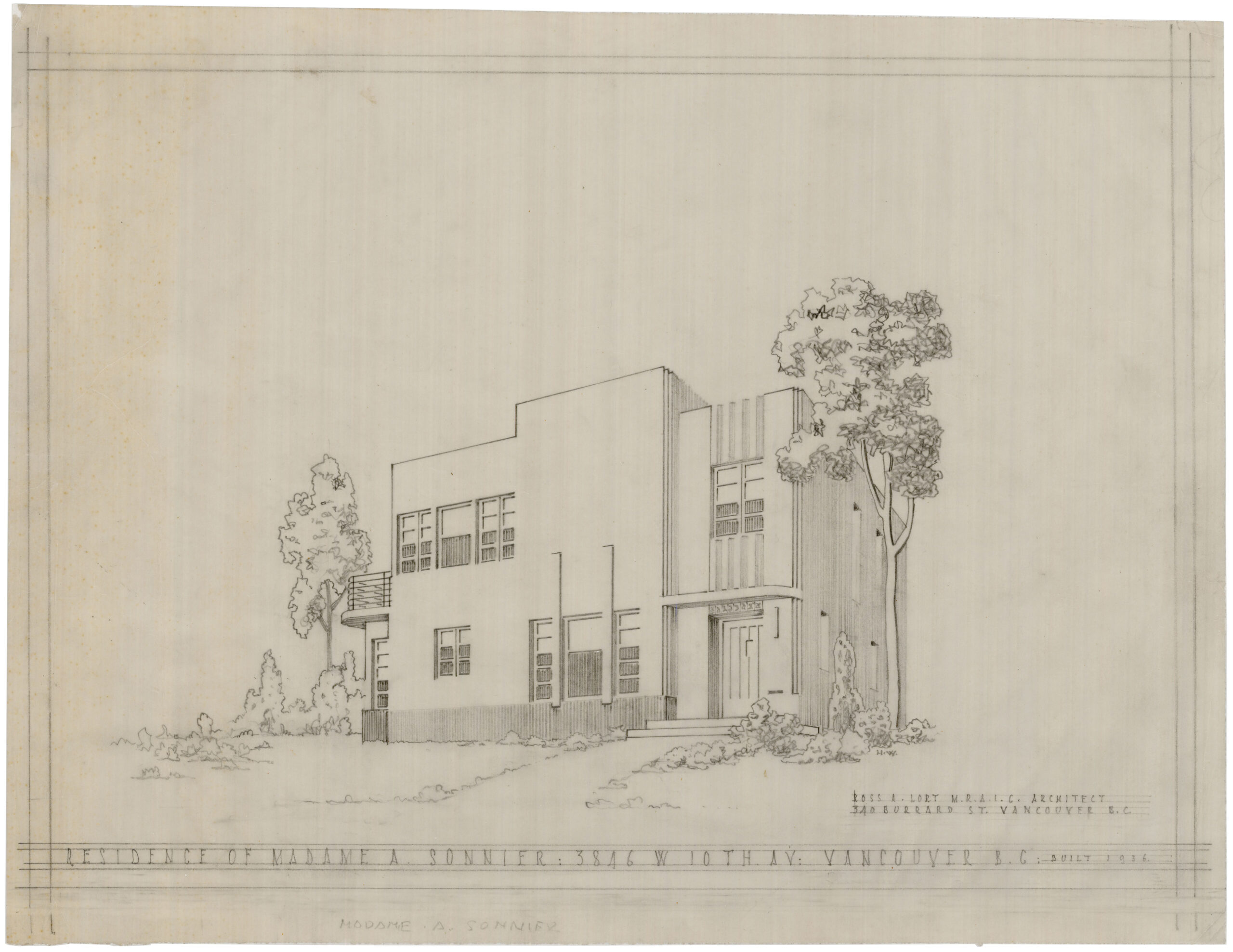

These later drawings are usually simpler and often less overtly decorative than the full-blown artistic renderings of the earlier decades, though they still exist to display the architect’s design to the client and others. The following drawing, by Ross Lort, is the first sheet in a set which includes elevations, floor plans and framing plans for a residence in West Point Grey.

While perspective renderings were originally created to serve a number of purposes during the architectural design process, for researchers they provide some of the most easily accessible documentation of our built heritage.