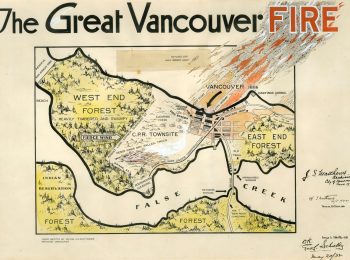

As you move through the urban landscape, you may have wondered about the structures around you, their history, the reasons why they were built, and by whom. How often do you also ponder what other structures may have been proposed for the same area or to fulfill the same function, but were for one reason or another left on the drawing board? And if you do ponder this, how do you search for something that never was?

![An example of the built and the unbuilt – where the reality of what came to be was quite different than one vision. Vanier Park as seen in 1971 from Burrard Bridge (left), and a proposed [unbuilt] industrial version of the same area, 1917. Item numbers: CVA 23-39 and CVA 380-1](https://www.vancouverarchives.ca/wp-content/uploads/1_Vanier-park.jpg)

This was the question I mulled during the process of completing my Archives and Records Management MLitt dissertation. Specifically, I was looking at how users of archives (aka researchers) and information professionals (aka archivists) discover and search for unbuilt design records in archival holdings, how archival descriptions may help or hinder this process, how researchers and archivists make use of these records, and then ultimately the value researchers and archivists place on these types of records.

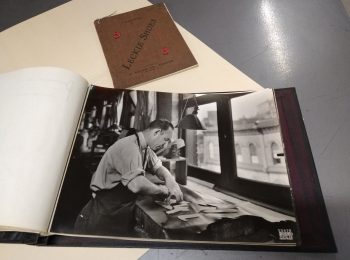

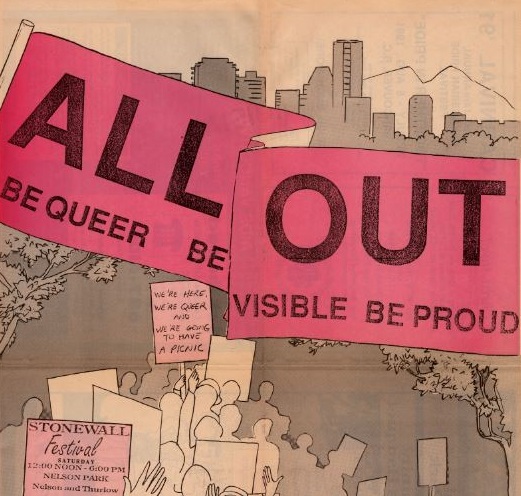

The long and short of the research was that it takes a variety of strategies to search for these types of records (as with any topic), including talking with archivists about one’s research, conducting keyword searches, and thinking about what types of records may contain the information one is seeking. These types of records can (perhaps not surprisingly) be more work to locate because of their nature (i.e., unrealised designs) and because of a variety of challenges related to catalogue descriptions. However, when located, researchers and archivists used them in many different ways, including for academic use, architectural research, exhibitions, teaching, and exploring the what ifs and whys. These types of records often prove to be intellectually stimulating, give insight into why designs did not develop to maturity, provide information about the process of design, help reveal the social, political and economic priorities of an era, and of course those that are visual can be valued for their aesthetic and artistic qualities.1

All of this is by way of introduction to a few blog posts where we will be highlighting some of the unbuilt design records that we hold at the Archives. Back in 2017, Digital Archivist Sharon Walz wrote about Vancouver’s unbuilt leisure palace, which she found during some rehousing activities. In keeping with the park and recreation theme, I draw your attention to the Mawson plan for Stanley Park.

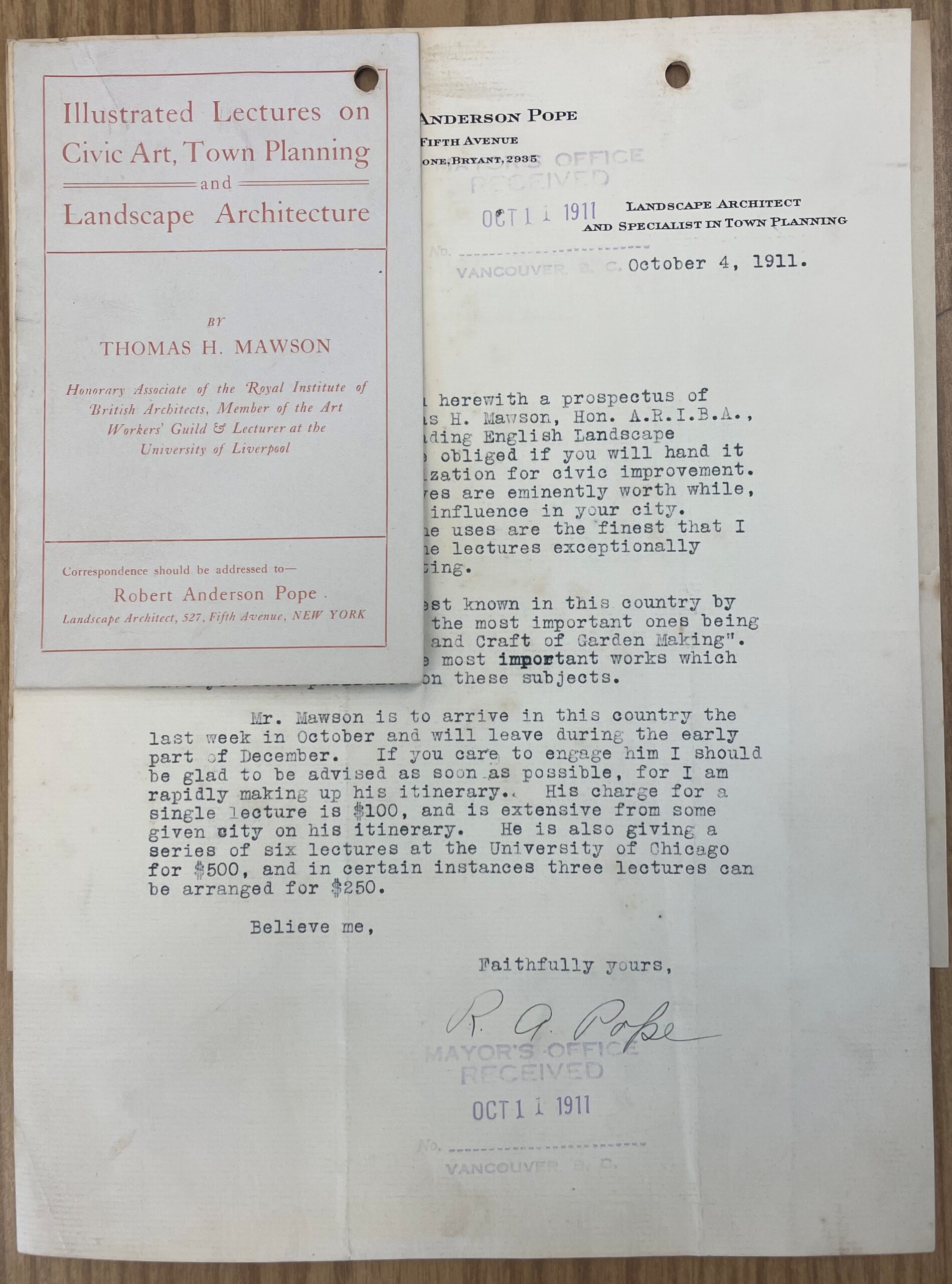

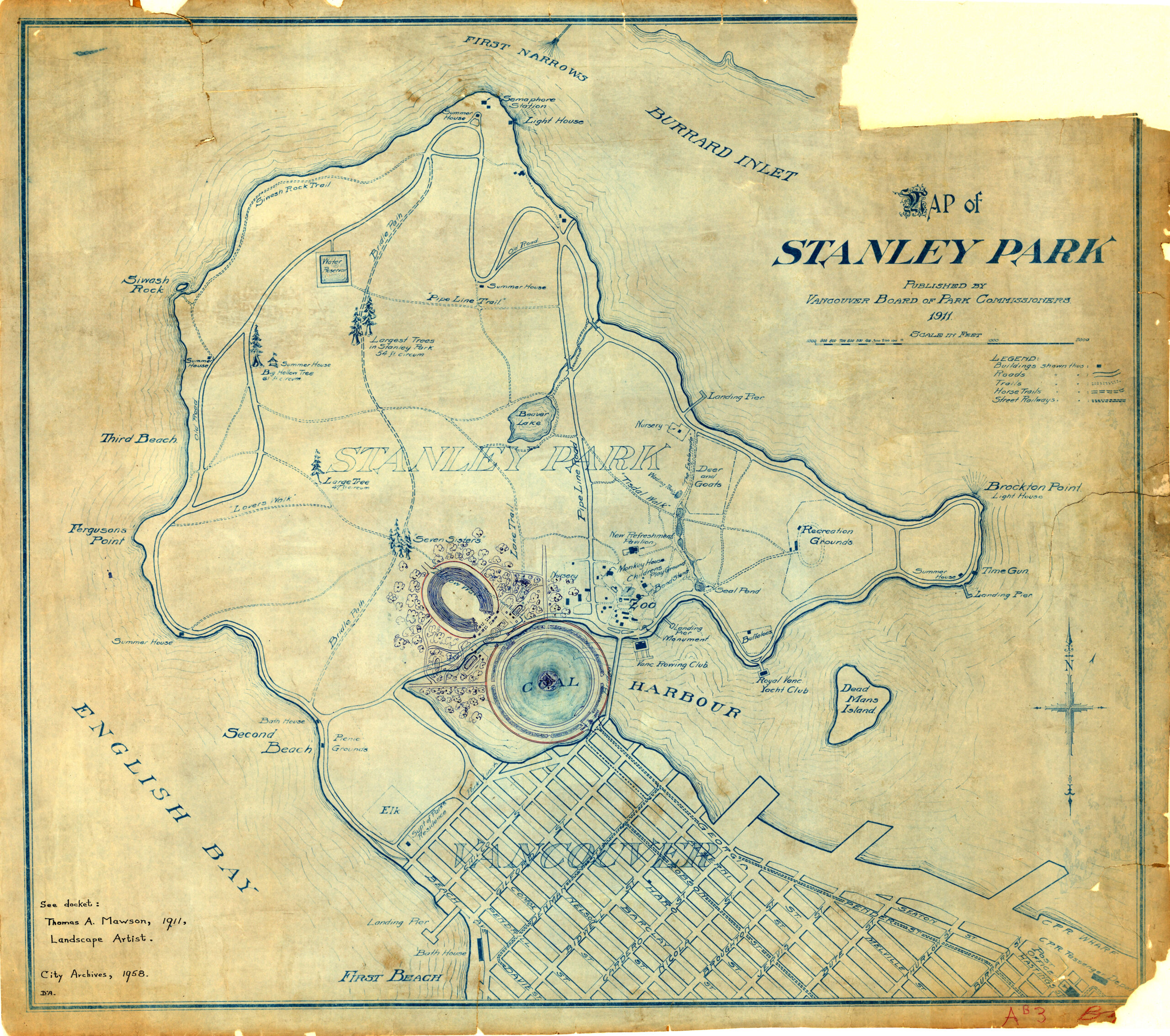

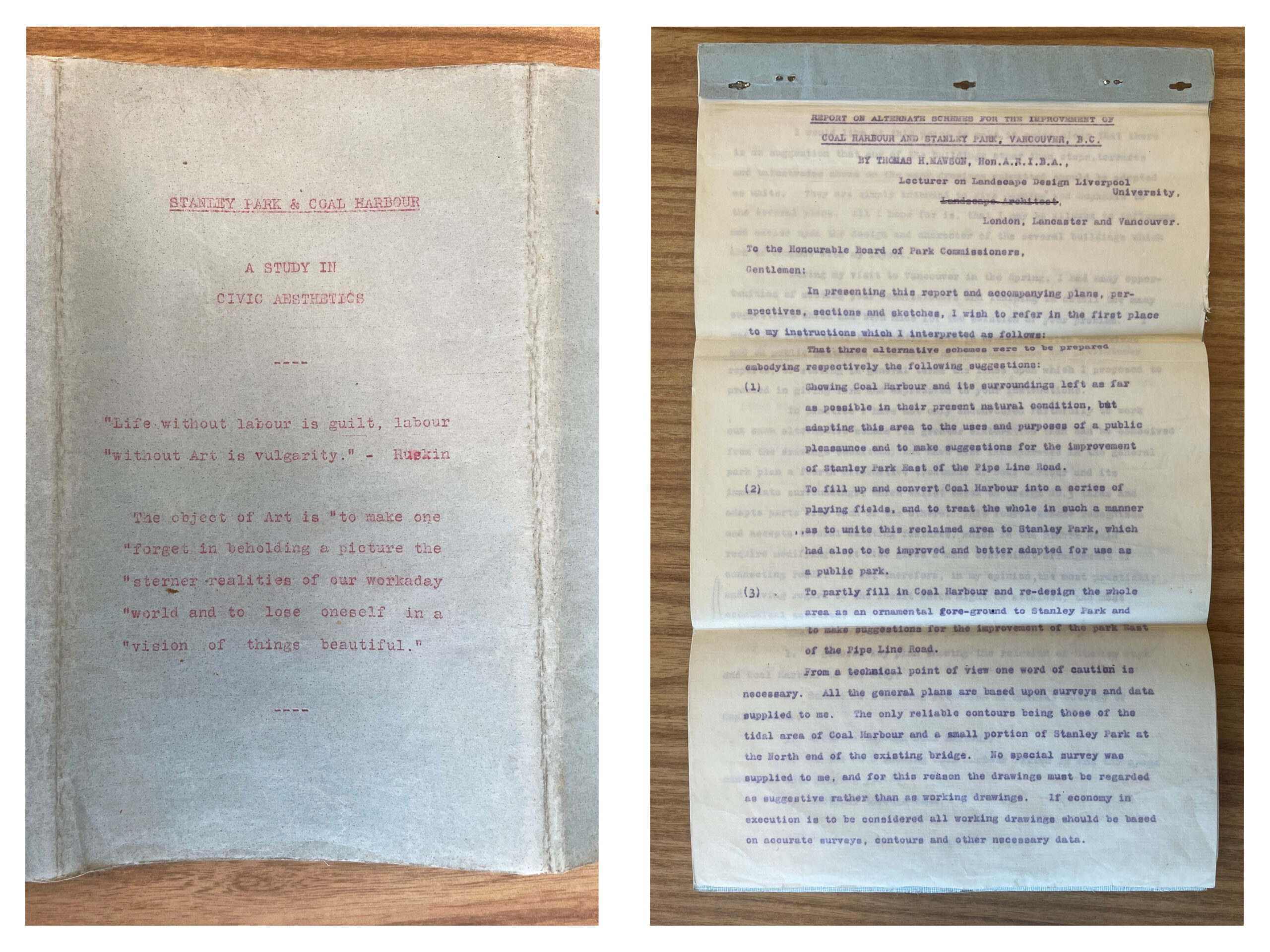

Late in November 1910, discussion regarding engaging a landscape architect or other qualified person to draw up plans for improvements in Coal Harbour that would coincide with the upgrades to the Stanley Park causeway was recorded in the Park Board minutes. About a year later, the Board was informed that Thomas H. Mawson, well known landscape architect from England was touring Canada on a lecture series.2

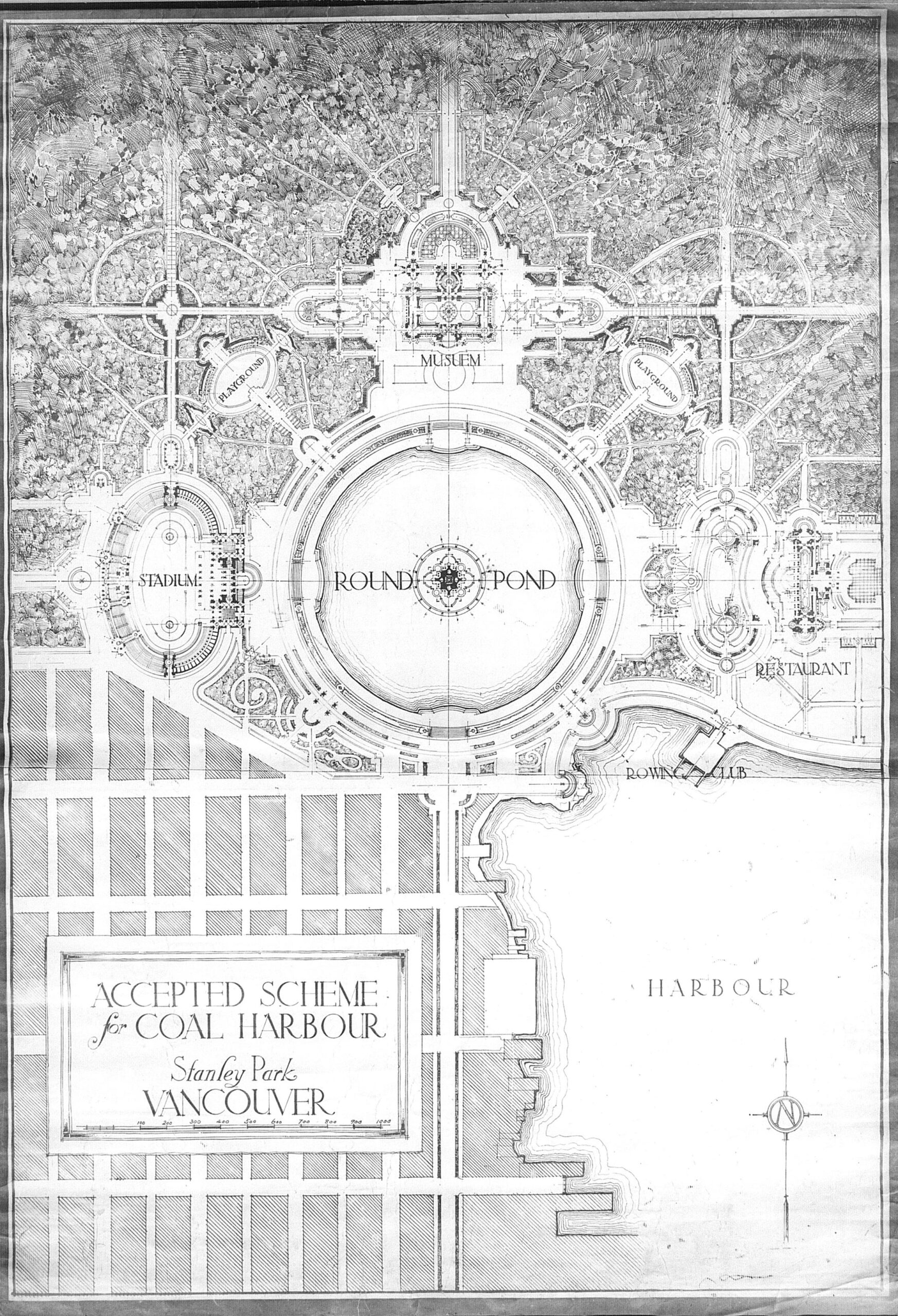

The Board contacted and secured Mawson’s services in early 1912, requesting that he produce three schemes–the first a landscape plan with minimal intervention or “improvement” of the area focusing on only lake formation (i.e., Lost Lagoon). The second was a ‘total fill improvement’ scheme where the lagoon would be filled in and turned into playing fields. This was clearly Mawson’s least favourite directive, describing it in his October 16, 1912, report that “From an aesthetic standpoint the adoption of this scheme would destroy every opportunity which this area gives for securing the ‘grand’ impression of a noble entrance to a great park.”3 The third was a “partial fill improvement” with the re-design of the “…area as an ornamental fore-ground to Stanley Park…”.4 Mawson presented his three schemes, plus an additional fourth scheme – a scheme based on Scheme no. 3, but one that ‘…takes and adapts parts from each of the others’ – to the Board in September.5 He favoured Schemes no. 3 and no. 4, which envisioned the area as a Civic Centre with ‘Georgia Street as the great axis’, connecting the city with the park, and providing the park a grand entrance way.6

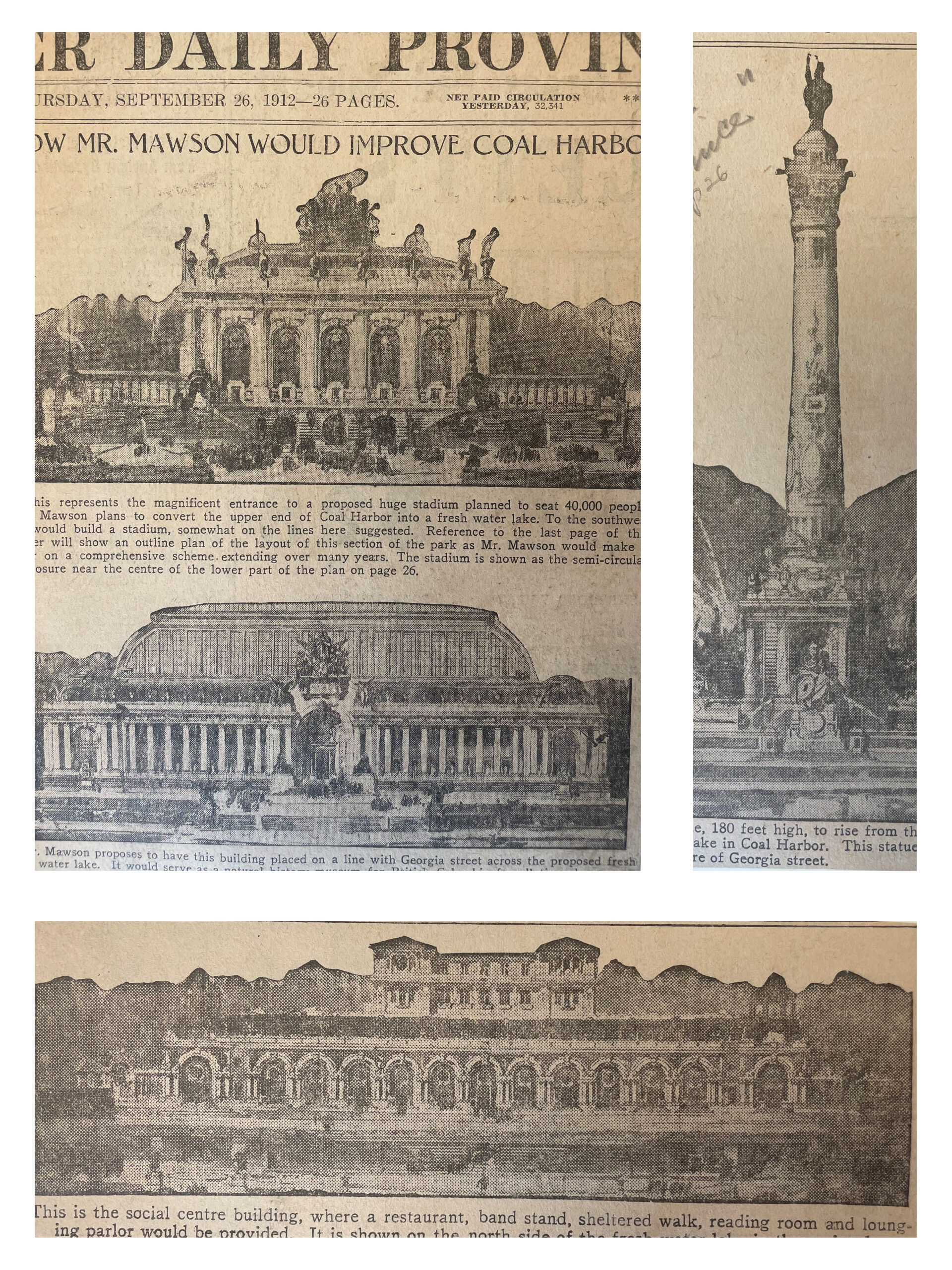

Over the next month, the schemes were publicized through a series of lectures and displays, and included layouts, perspectives and elevations. The buildings he proposed were grandiose and neoclassical designs, and he envisioned a Nelson’s column-like structure in the centre of the lake with a statue of Captain Cook or Captain Vancouver atop. In Mawson’s report, the details of the fourteen drawings presented are listed; however, the Archives only has visual record of many of these drawings in the newspaper clippings that Major Matthews, the first City Archivist, saved regarding the project.

When Mawson presented his ideas, he asked that “…you not be appalled by the comprehensiveness of any of the schemes, but to regard them as suggestive policies of development, any one of which may require twenty years or even more for its realization.”

On October 23, 1912, the Board resolved that Scheme no. 4 should be adopted. A slight modification to this scheme was made in the ensuing weeks, swapping the location of the stadium with that of the museum, a decision endorsed by the Board. A copy of a December 16, 1912, agreement between Heath & Gore, a Tacoma-based architecture firm, Ormond & Godfrey, a Vancouver-based engineering firm and the City to build the stadium by raising money through public subscription is glued into the pages of the Park Board minutes confirming the resolution to adopt the modified scheme. The building of the stadium in Stanley Park seems to be the catalyst that provoked push back from various citizens, with an opinion piece published in the December 18, 1912, issue of the Vancouver Sun titled “Parks Board Folly”. In it, the writer states that a stadium should be built for the city, but just not in Stanley Park. The City Beautiful Association, which mounted a “Hands off Stanley Park”’ campaign to counteract the proposed stadium, formally stated their complaint at the December 30th Park Board meeting. It is interesting to note that when Mawson arrived in Vancouver, and just prior to creating the designs for Stanley Park, he strongly advocated that a stadium be located in conjunction with, or near what would become the railway terminus in False Creek.

However, by May 1913, Scheme no. 4 still had the green light from Council and the Park Board, and the Park Board requested that plans and information be drawn up for submission to the Minister of Militia and Defence, Colonel Sam Hughes, who had to approve the removal of any trees from the park for the erection of the buildings and other structures. The fourteen drawings were placed on display for the public at the Stanley Park Pavilion during the summer of that year. In December, the Minister confirmed his approval.

Very little, however, resulted from the drawn plans. The 1913 economic depression would have curbed any enthusiasm to implement the designs. Mention of them drops from the Park Board minutes until the spring of 1914, when Mawson requests the loan of his drawings to exhibit at the Town Planning Congress and Exhibition held in Toronto. Presumably, at least the Scheme No. 4 drawing stayed with Mawson and returned to England, as correspondence sent in May and June 1917 between Mawson and the Park Board indicate that the Park Board wished to have the drawing back, but both parties were resolved to postpone the return ‘until shipping conditions [were] more favourable’, presumably once the war ended.

(1) If I haven’t completely bored you with an overview of my dissertation, there are more details regarding the research on the Archives & Records Association’s Section for New Professionals blog – Left on the drawing board: Unbuilt design records in archival holdings

(2) Mawson wrote The Art & Craft of Garden Making (1900), and Civic Art: Studies in town planning, parks, boulevards and open spaces (1911). According to the Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada, he was ‘an articulate spokesman for the “City Beautiful” movement in Canada in the early 20th C.’

(3) CVA, VPK-S81–, Loc. 048-E-01 fld 10, Coal Harbour – M, p. 10.

(4) Ibid, p. 10.

(5) Ibid, p. 2.

(6) Ibid, p. 7.

Could you imagine if Stanley Park was just an ugly industrial area right by the bridge? We love Stanley Park and can’t imagine it not being so close to home.