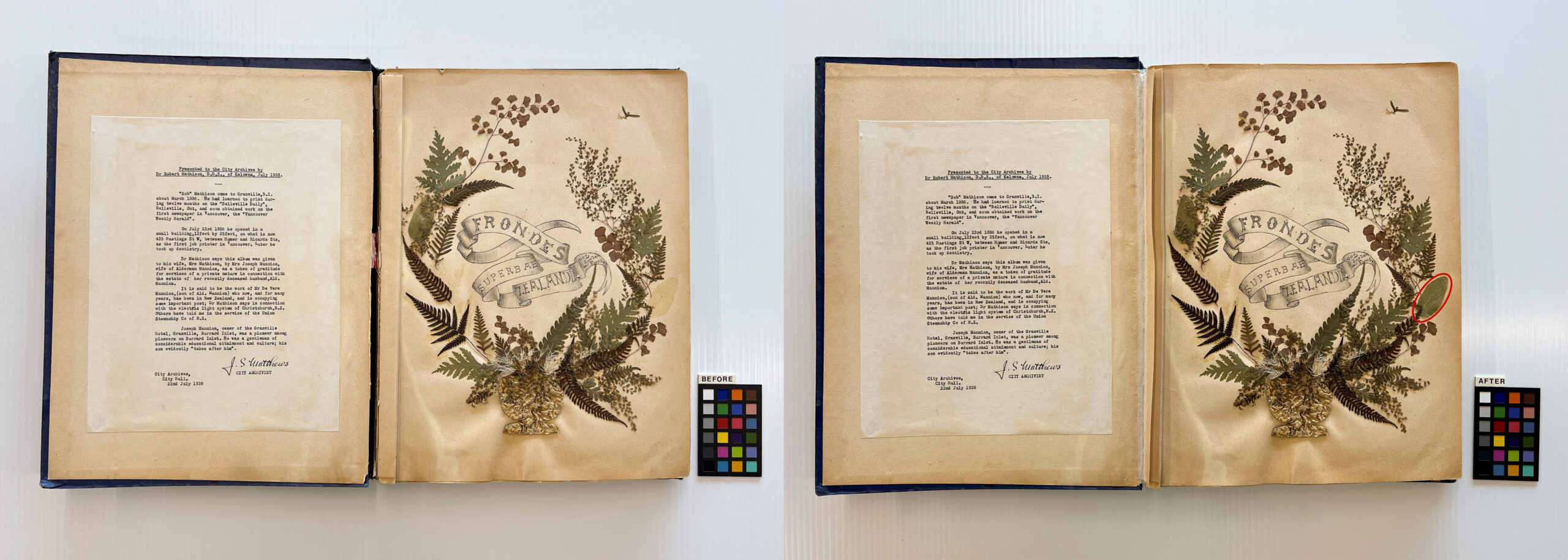

Picking up from our last blog post on the curious history of the fern album, for this month’s post, we will be taking a behind-the-scenes look at the conservation and digitization work put into making this unique volume available to the public. After the album was described by an archivist to make it discoverable on our database, it was clear that this would be a suitable candidate for digitization given the delicate nature of the botanical specimen pressings inside.

Conservation issues

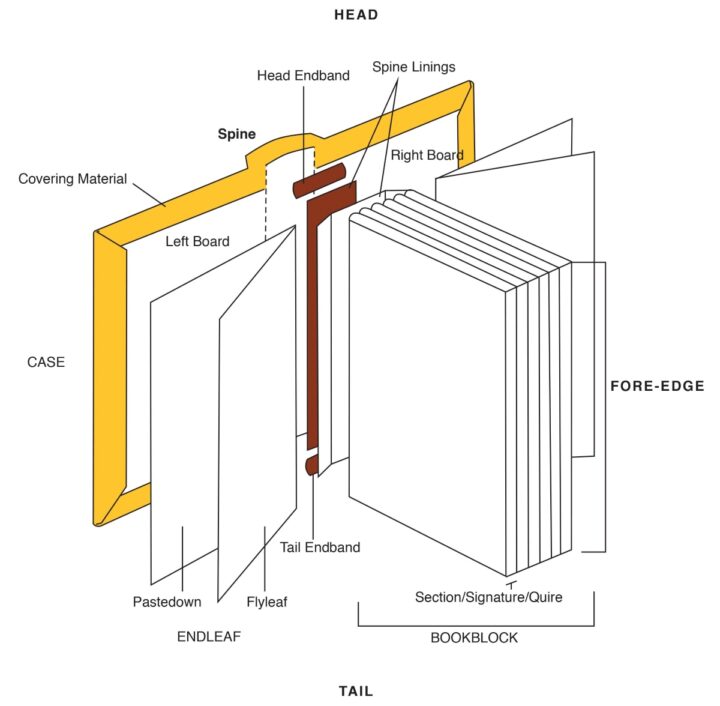

The fern album was in poor condition and conservation treatment was needed to stabilize it before digitization. There were conservation issues in both its structural integrity and overall aesthetics. These issues can be attributed to the construction of the album and damage sustained by wear and tear. Bookbinding-specific terminologies will be use throughout this post and the following annotated illustration on the anatomy of a book is included for reference.

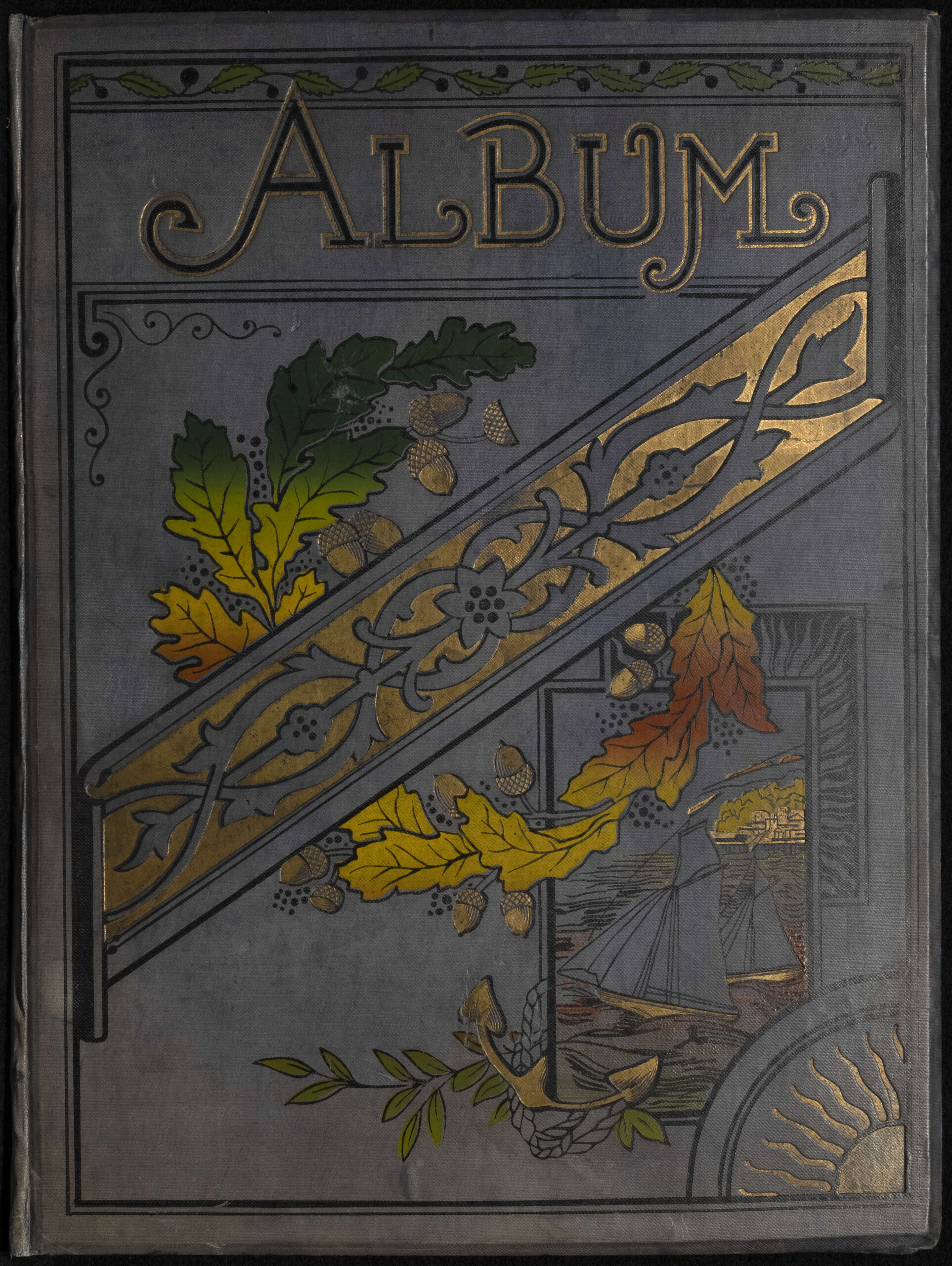

The fern album is a typical example of the type of albums sold commercially by stationers in the late nineteenth to early twentieth century. These mass-produced bound volumes were commonly made from papers and boards manufactured from wood pulp, which was preferred by paper mills for its low production costs and high yield. Paper-based materials made from wood pulp do not age well due to the presence of lignin, a naturally occurring organic polymer that forms the structural components in wood. As lignin breaks down with aging, it becomes acidic and accelerates the deterioration of the cellulosic chains in the paper, leading to yellow discolouration and brittleness.

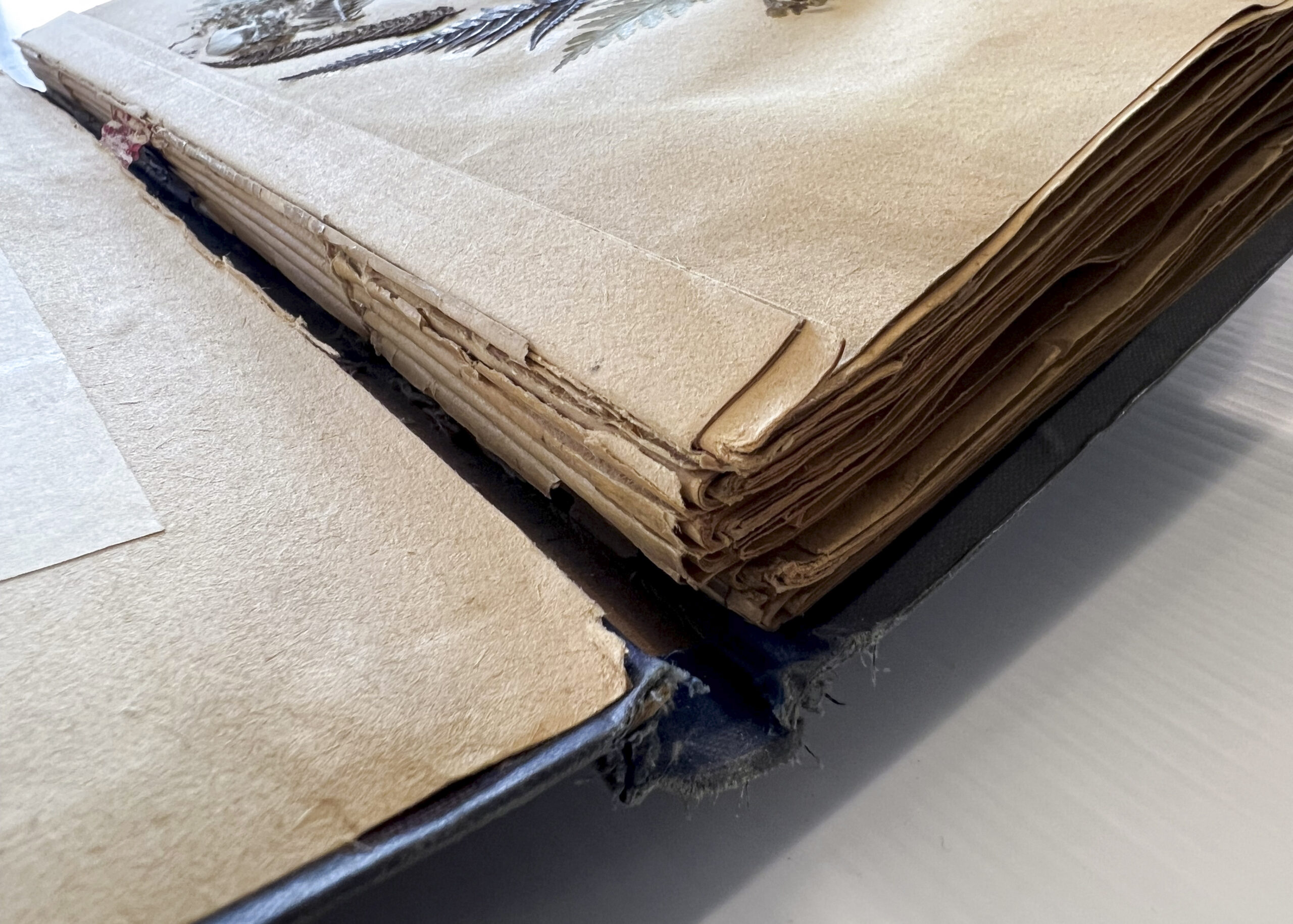

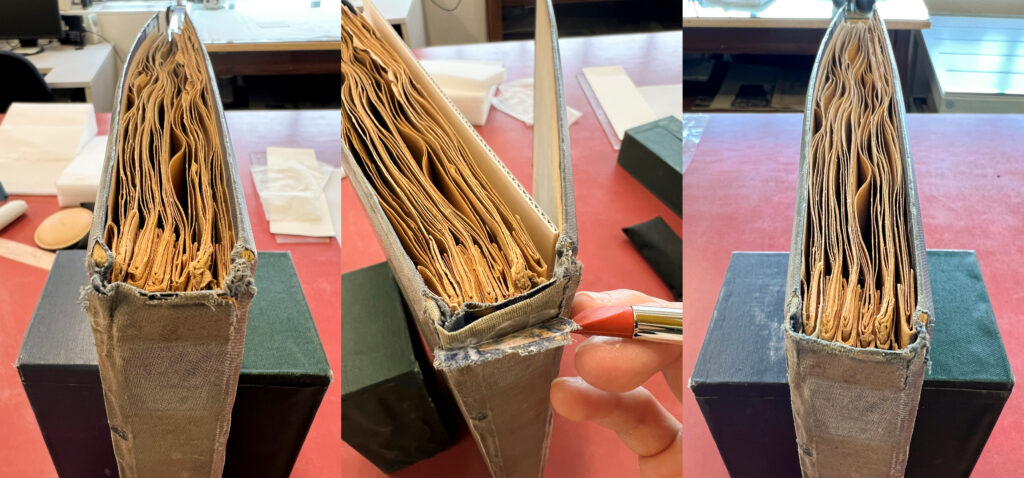

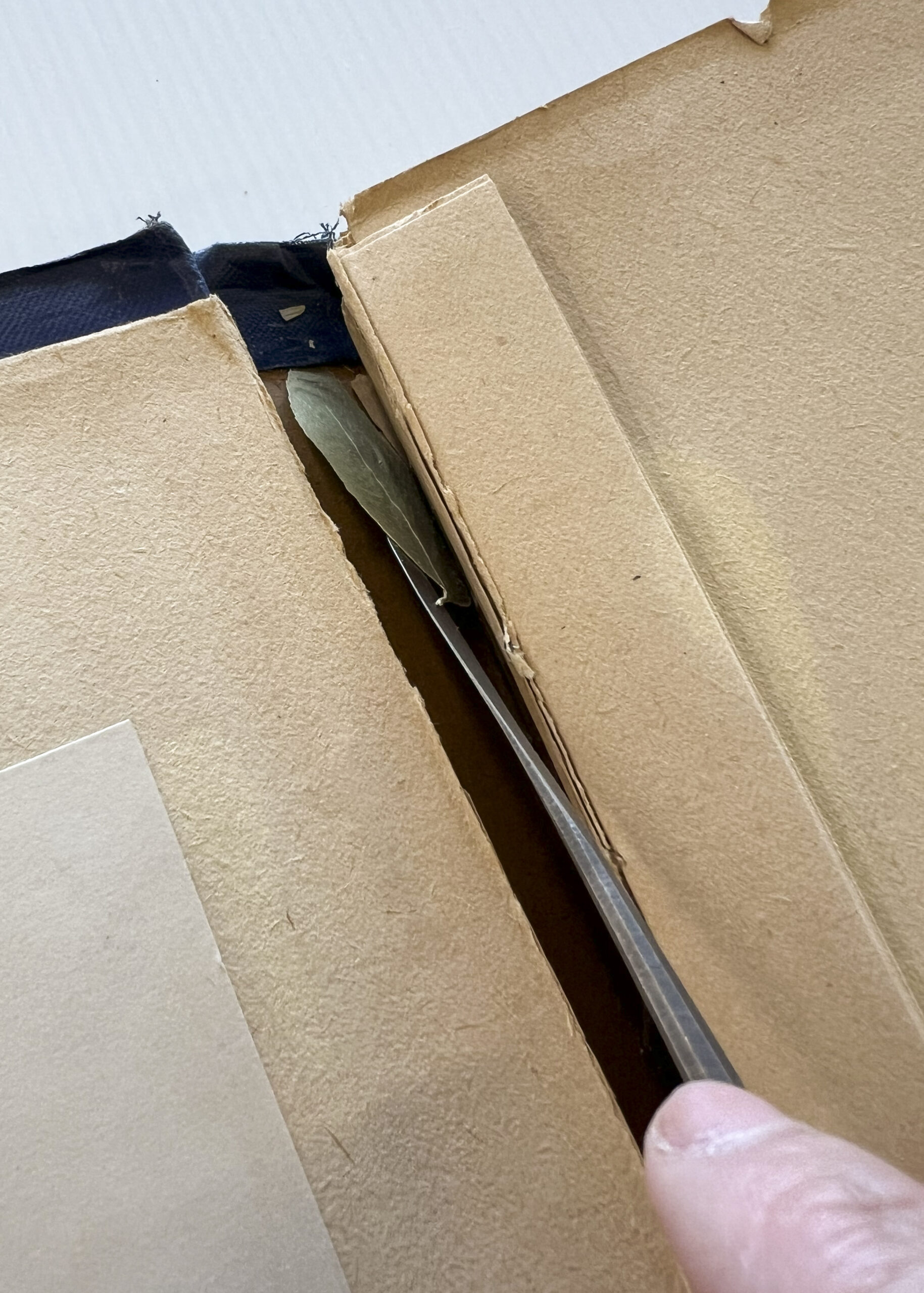

On initial examination, the most noticeable conservation issue with the fern album is the split at the front joint, where the sheet that doubled as both the pastedown and a leaf in the first signature had torn completely. The brittle paper made from wood pulp simply did not have the fold endurance to withstand the repetitive motion of opening and closing of the front cover, causing it to split eventually. The split also revealed the precarious attachment of the single sewing tape that is still holding the textblock together with the case.

The craft of gluing botanical specimen pressings onto the pages of an album is also intrinsically problematic for multitude of reasons. The animal glue used for pasting introduced excessive moisture to the paper resulting in cockling. These deformations created recessed pockets in the paper where airborne dirt can accumulate over time. The pressings also added bulk and rigidity to the paper and were prone to peeling off when the page was turned and the paper was flexed.

Conservation treatment

Here is a brief breakdown of the key treatment steps carried out in stabilizing the fern album before digitization.

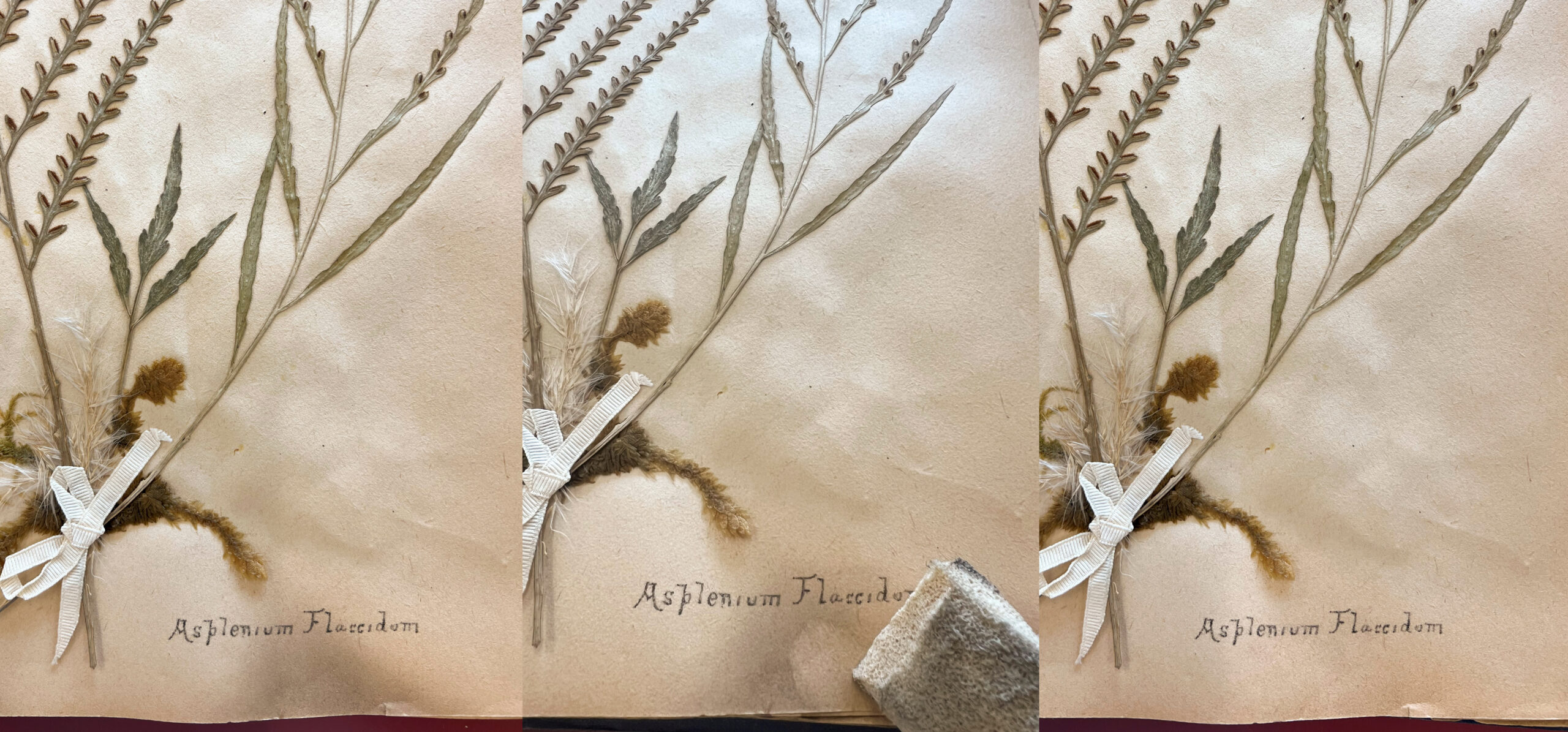

The fern album was dry surface cleaned with a chemical sponge followed with a soft hake brush on both the covers and the textblock. Localized areas with stubborn engrained dirt required additional cleaning using various other dry-cleaning tools. Extra care was taken to avoid rubbing off the titles (scientific names) inscribed in graphite.

The brittle, short-fibred wood pulp paper was very susceptible to tearing, especially where the leaf was not squared in the textblock, exposing the paper past the protection of the covers. Tear repairs were done with wheat starch paste and various Japanese tissues to match the colour and thickness of the original paper.

Small losses in the bookcloth covered boards and spine were filled with a new sympathetic bookcloth. The dented and delaminated corners in the cover boards were also consolidated with an archival-quality polyvinyl acetate (PVA) adhesive.

Under close examination of the back joint that was still intact, the pastedown was revealed to be the same single sheet as the sixth page in the adjacent signature. This binding structure is different from the conventional practice of using the same sheet for the pastedown and the flyleaf. By counting the sixth page from the first signature, the other half of the sheet split from the front pastedown was identified. A long-fibred Kozo Japanese tissue was used to create tabs to reattach the textblock to the front cover. An additional guard was added to reinforce the front joint, but to also mask the gap that was partly caused by the split and partly by a pre-existing loose sewing structure.

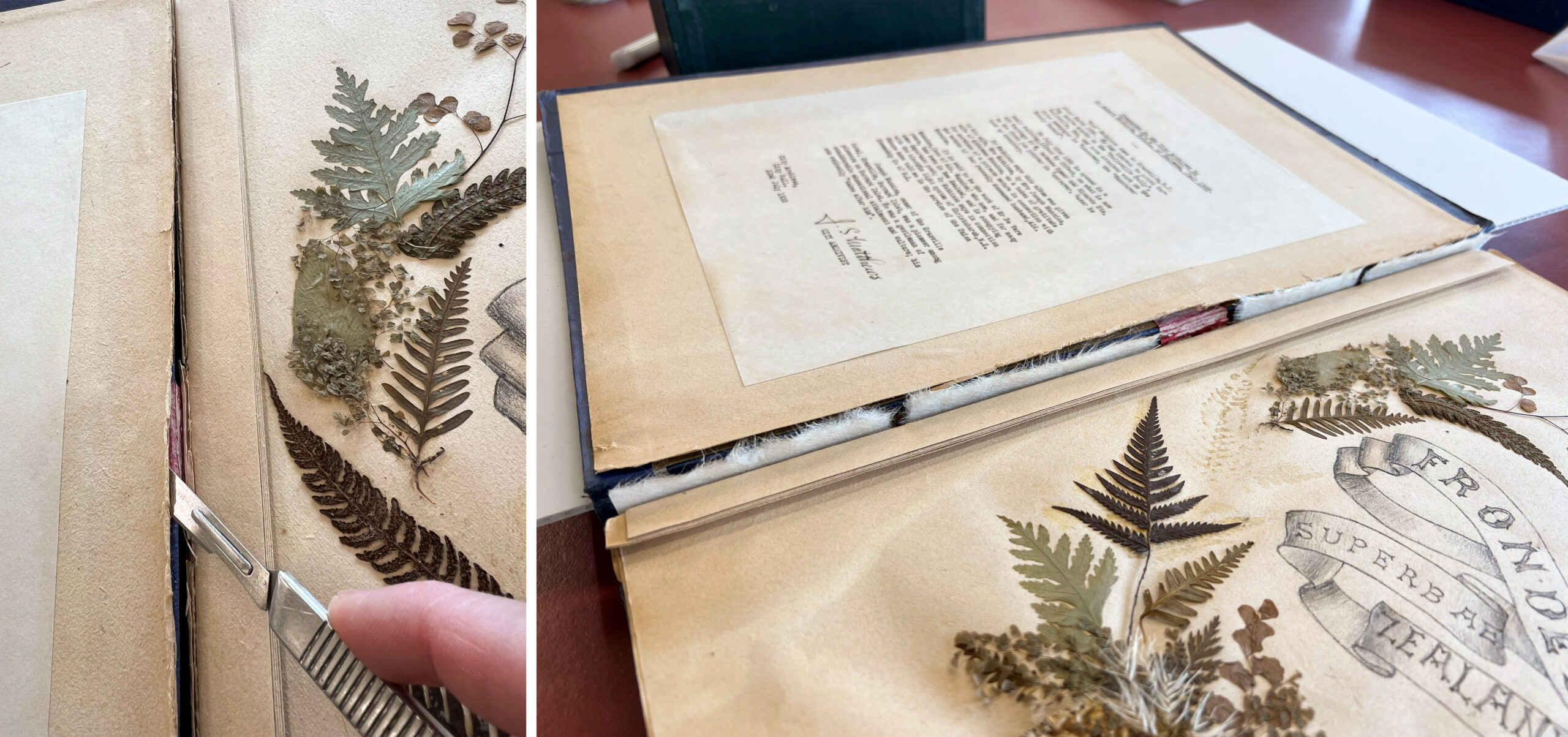

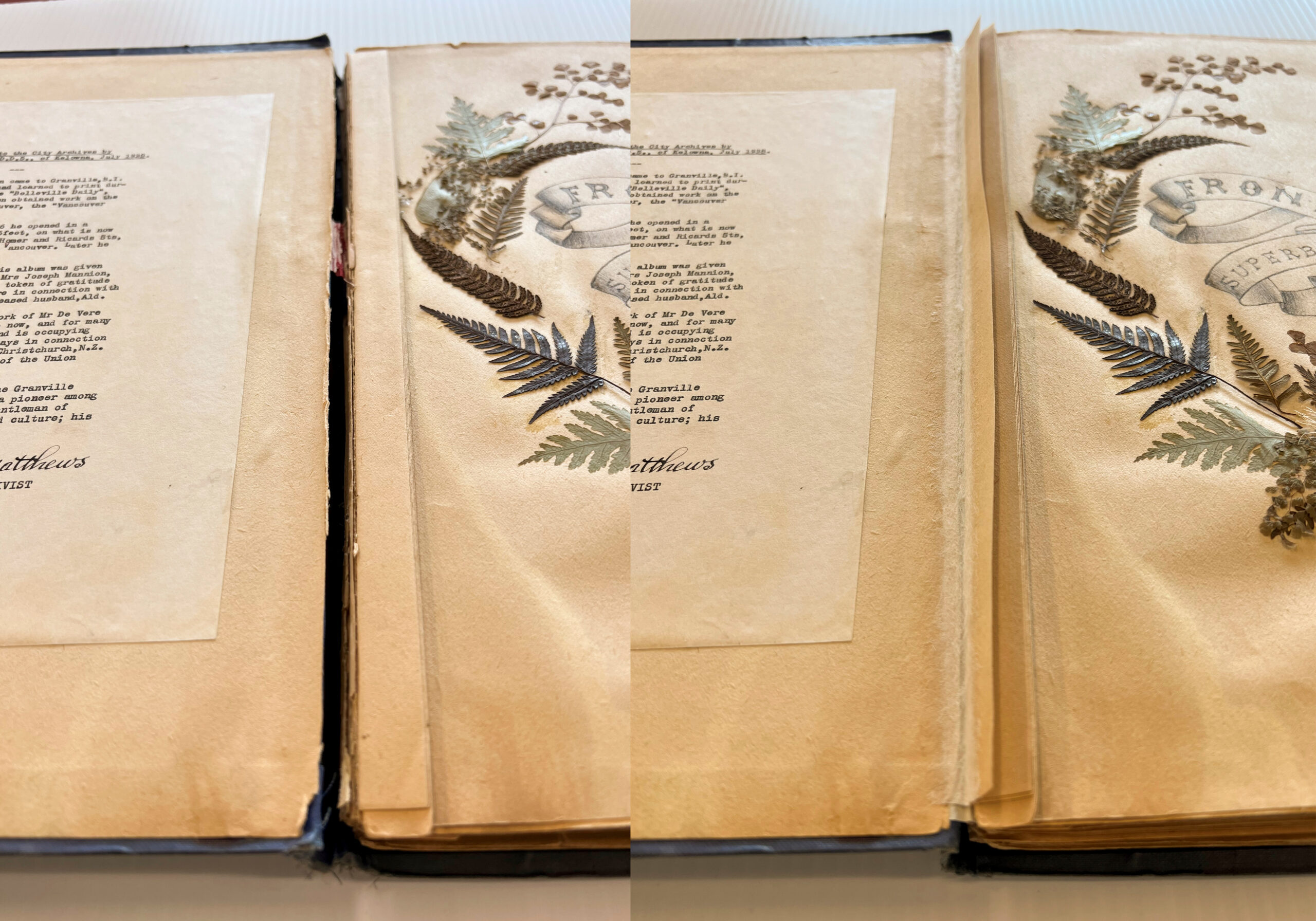

A small number of the botanical specimen pressings peeled off as the adhesive became brittle with aging and failed. The original placement of the large loose pressings was easy to identify and were re-adhered with wheat starch paste. Many small loose pressings were found trapped in the gutter and re-adhered where their original placement was obvious. For loose pressings with ambiguous original placement, they were encapsulated and kept alongside the album for posterity. One of the most satisfying discoveries in this treatment was finding a loose leaf in pristine condition, tucked between the spine and the textblock, that coincidentally happened to be the perfect match to the shape of an adhesive residue on the cover page.

Digitization

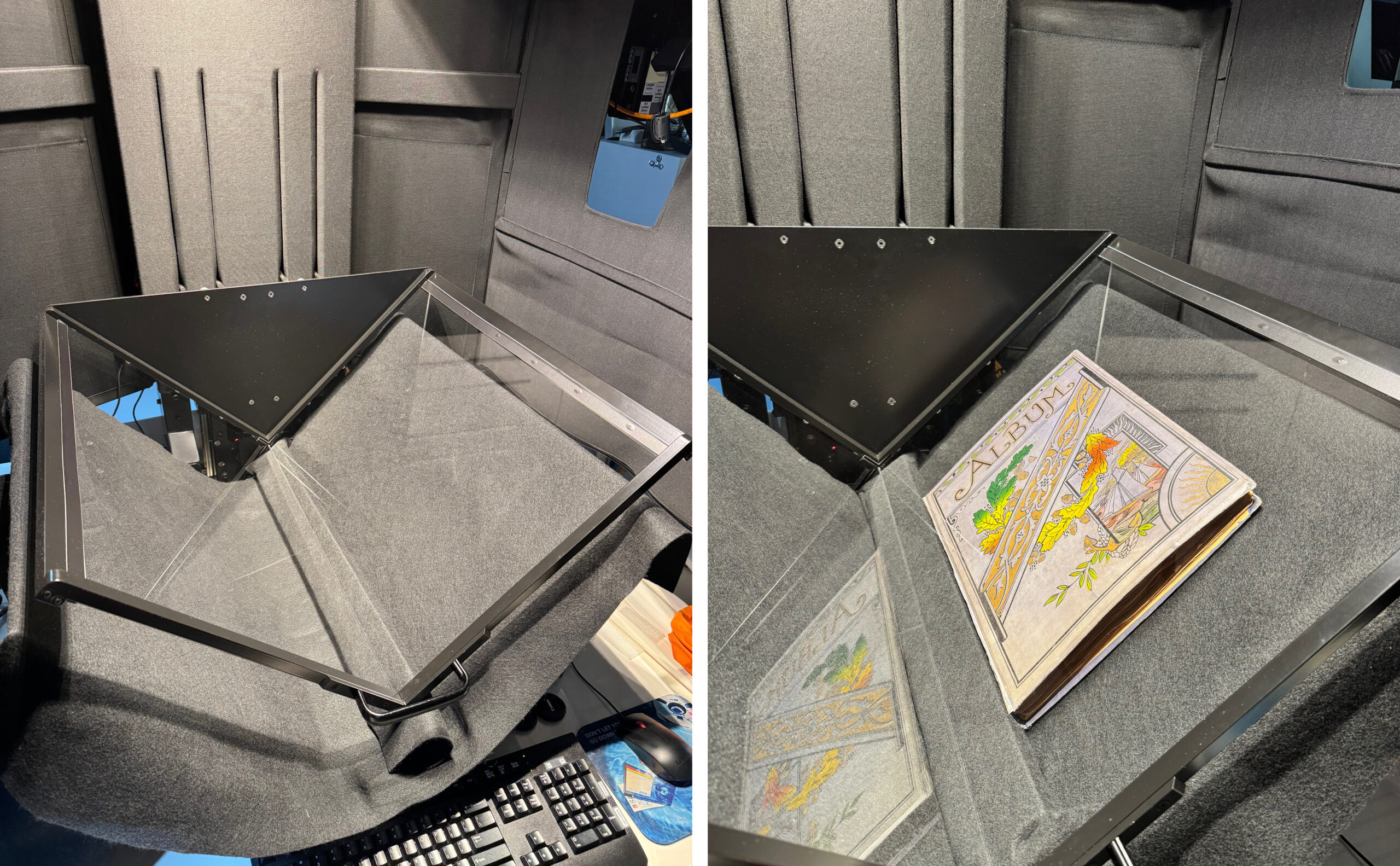

Digitizing the fern album served as an excellent case study for exploring the capabilities of our Atiz book scanner beyond our usual City Council Meeting Minutes series (COV-S31). Rather than capturing pages of text, we photographed the album from cover to cover in its entirety. While we typically shoot in large JPEG format, for this project we used RAW to capture the intricate details and colours of the botanical specimen pressings. The results were impressive: zooming into the images revealed fine details not easily visible to the naked eye. Below are two examples highlighting the delicate spores and the almost crochet-like texture of the ferns.

![Detail from Todea superba [Leptopteris superba]. Reference code: AM1444-: LEG4839.1-: LEG4839.1.05](https://www.vancouverarchives.ca/wp-content/uploads/LEG4839.1.05-detail.jpg)

To photograph the fern album effectively, we had to adapt our usual setup. We wanted a rich, dark background for contrast and a supportive ledge for the spine, allowing us to capture both covers without the platen obscuring any part of the image. This involved draping black felt over the book scanner cradle and wrapping a foam block to provide additional support. The foam block allowed the “V” of the platen to sit just below the edge of the book, keeping it out of the way of the shot.

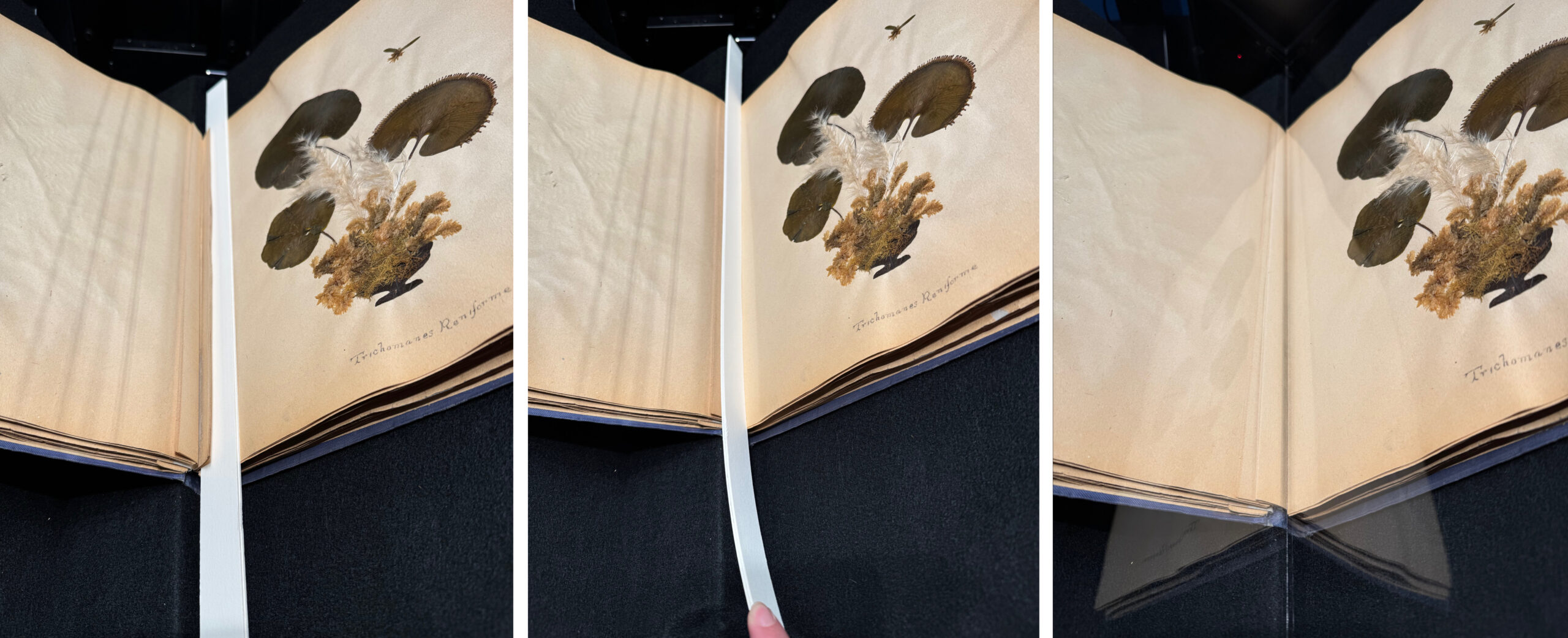

On some pages, the v-hinges holding the signatures together were visible, which posed a challenge, as we didn’t want to capture them in our shots. The platen lowers vertically onto the pages, making it impossible to manually hold down the hinge during capture. To address this, we cut a thin strip of matboard that could be slipped behind the hinge and gently flipped away as the platen came down, isolating it from the page. After the platen settled, we carefully slid the matboard out to get a clean image.

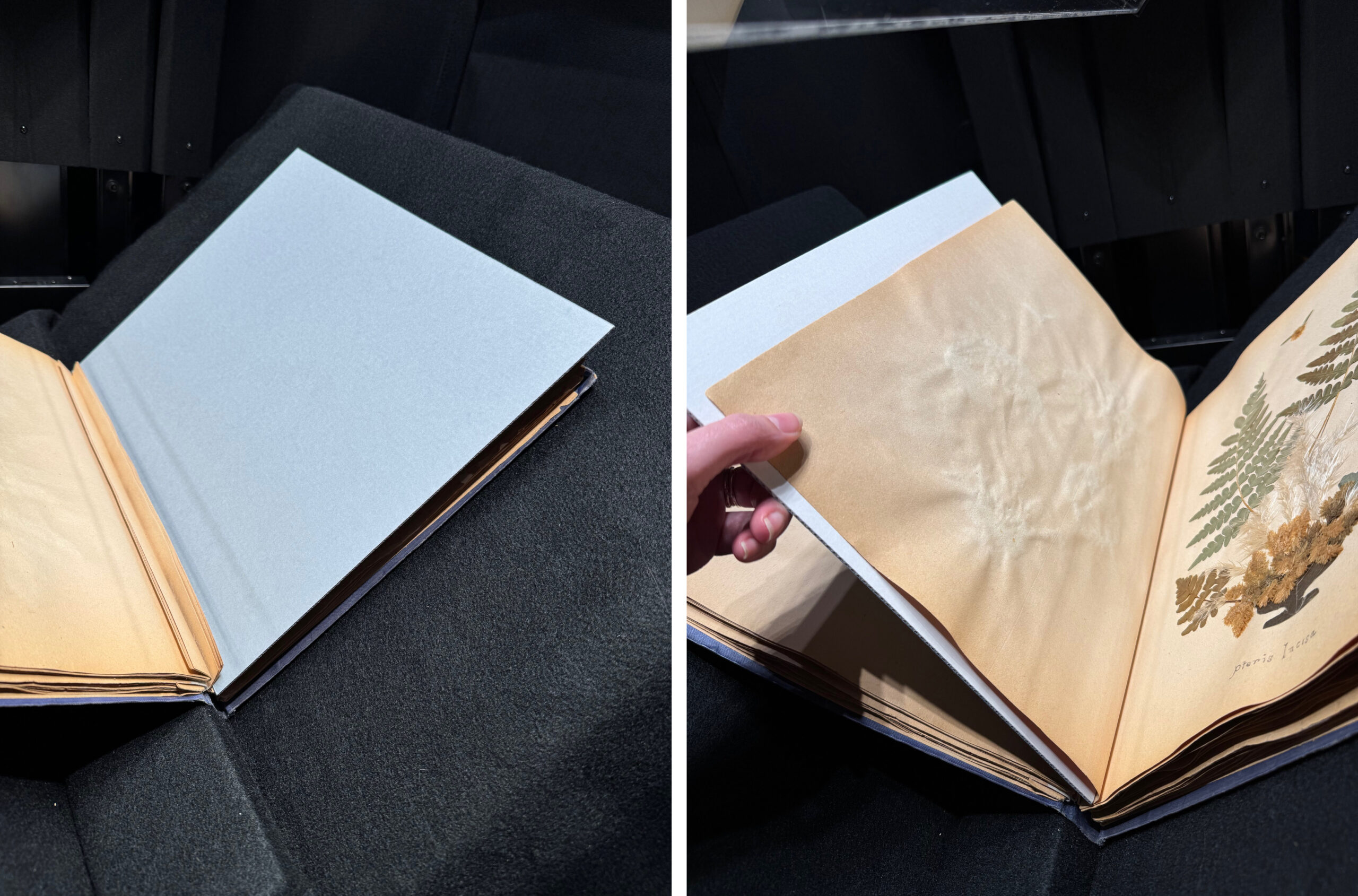

Preserving the integrity of the specimens meant finding a gentle way to support and turn the fragile pages without dislodging any of the pressings. We achieved this by using a full sheet of rigid archival corrugated cardboard to rest the pressings against and to provide a uniform support when turning the pages.

We are excited to share with the public this hidden gem on our database, where each page of the album is now available to view and download at high resolution. We hope that researchers will be as awed as we are by these artful interpretations of botanical specimens that travelled across the ocean from over a century ago.

Editor’s note: If this has piqued your interest in botanical specimens, Kew Gardens has digitized millions of specimens in their collection. You can read more about their project here and visit their database landing page here. We did an image search for one of the specimens in our fern album, leptopteris alpina, and got these results.

fascinating and fantastic work! well done. and thank you for such a clear report of your processes.